A teenager once told me that, when he moved to Miami, he “thought everyone would look like Sofia Vergara.” He was surprised, and a little disappointed, to find that people here looked – normal. He was expecting all the hypersexualized Latinas he’d seen on TV.

I didn’t have to ask what he meant.

Miami, also referred to as the capital of Latin America, has a reputation. It always has. The 1980s introduced us as the violent world of Al Pacino’s Scarface, awash in cocaine and criminal refugees, and then as a glamorous mecca for vacuous beautiful people looking to indulge in the city’s lawlessness.

Then in the nineties, Will Smith immortalized it as “the city where the heat is on,” where “the ladies are half dressed, fully equipped,” and “the hot mamis” are “screaming ‘¡Ay papi!’”

Unlike Los Angeles or New York, Houston or Chicago – all cities with large Latino populations – the perception of Miami has worked to introduce and reinforce stereotypes, especially for Latinas.

Even as society begins to grapple with the aftermath of #MeToo and with how women – especially young women – are treated and portrayed in media, Latinas more often than not are portrayed as bombshells: fetishized. These roles are for hypersexualized Latinas, wearing tight clothes and heavy makeup.

Although Sofia Vergara had many acting roles, it was her portrayal of Gloria Prichett in the ABC hit Modern Family that made her a star in the United States. Notably, in order to fit the role of a Latina on mainstream US media, the Colombian actress had to look less like herself, dyeing her naturally light hair and getting made up to look darker, more “tan.”

Her character – a sexy, voluptuous woman – was often the butt of jokes. She was, after all, the foreigner. She was loud, heavily accented, and trying to fit into a white, suburban, North American life that she didn’t totally understand. She was the beautiful trophy wife to a wealthy man, old enough to be her father; but, perhaps to soften her image, she also happened to be a loving, doting mother – and so playing into another trope.

Infantilizing while also sexualizing women is certainly not a new trend. The hypersexualized Latinas trope is popular because it plays to that. Their characters are desirable but aren’t trying to be desirable. It is a surrender to, or maybe an ignorance of, their power.

And so it’s interesting that when Latinas actively construct their image, when they seem to not only control but also enjoy their sexuality, that is not as well accepted. It doesn’t play into the fantasy.

If a woman has the audacity to be sexy, and to enjoy the attention, to dress and dance provocatively – because she wants to, it’s obscene. If that woman not only speaks with an accent, but also celebrates her culture, her language, her heritage, then that is vulgar.

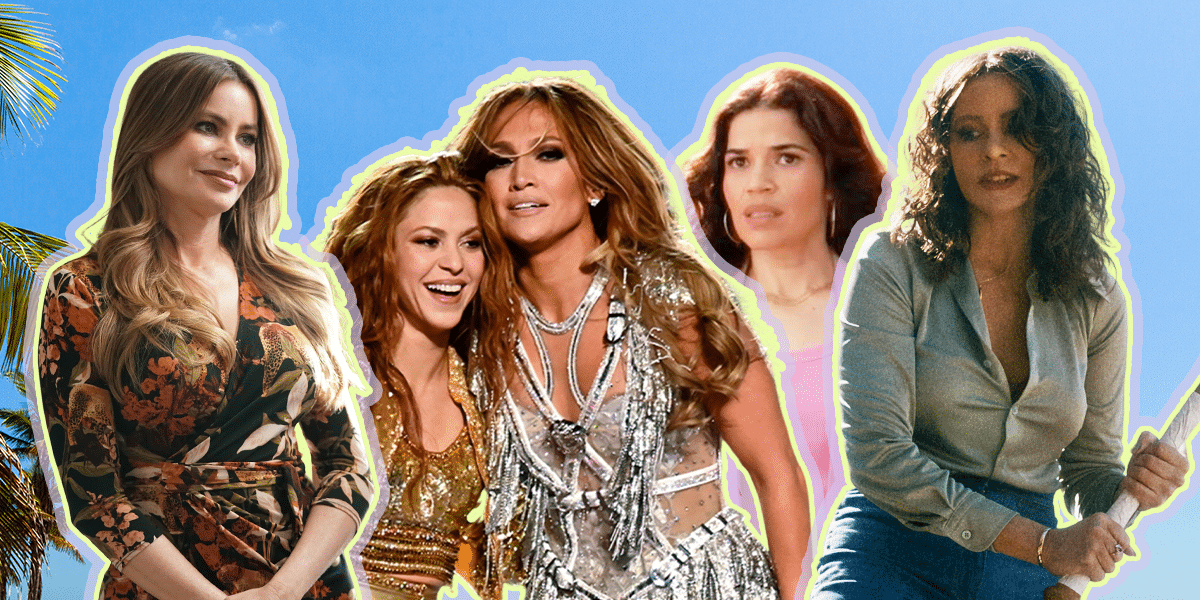

Take for example, Jennifer Lopez and Shakira, who also called Miami home. They are two of the most famous Latinas in the United States. When the stars performed together at the 2020 Superbowl Halftime Show, they were sexy. The performance was heavy on glitter and dancing, percussion, and spectacle. These two women owned the stage – and they seemed to enjoy it.

Perhaps that is what was so offensive.

That night, the Federal Communications Committee (FCC) received over 1,300 complaints. Apparently, people were scandalized. The performance, they complained, was obscene, too sexual, too explicit.

Too explicit for a Superbowl halftime show? Because although they wore more clothes than the typical football cheerleader, they were too unapologetically proud of their roots, they looked to be having too much fun.

It’s a point that America Ferrera’s character, Gloria, makes in Greta Gerwig’s blockbuster Barbie. Her monologue, which earned her an Oscar nomination, spoke to all women, but coming from Ferrera – who got her start in Real Women Have Curves and then achieved fame with ABC’s Ugly Betty – it was all the more powerful. What better example of the monologue than Ferrera’s real life?

We are supposed to be exotic, desirable, and passive. Hypersexualized Latinas are rendered powerless.

Which is why Vergara’s latest project is even more interesting. In Griselda, the Netflix miniseries based on Griselda Blanco aka “the Godmother” of Miami’s drug empire, Vergara works to show her range as an actor. She wanted audiences to forget about Gloria Prichett. She worked to portray a woman who was ruthless and brazenly hungry for more power.

It took three hours in a makeup chair – applying prosthetics, a wig, and a costume – to look less like herself. But, while there is little trace of Gloria Prichett, there is no trace of Blanco. Presumably, Netflix executives wanted to keep enough of Vergara’s beauty to still attract audiences. After all, an older, matronly Latina can want power, as long as it’s not sexual power.

At its core, that is what Griselda, the series, is: the story of a woman’s struggle for power, money, and status. Griselda Blanco shattered stereotypes. She was a ruthless criminal, a drug trafficker, and a murderer. The series, however, also focuses on Blanco as a single mother who fought to escape an abusive relationship, finding herself enmeshed in the drug world, and then fighting to establish herself as a force in a violent, male-dominated world.

This is not the first series seeking to understand or add dimension to villains. From The Sopranos to Breaking Bad, Hollywood is fascinated with the inner workings of bad guys.

But, in order to humanize Griselda Blanco – to add some dimension and complexity to the “Godmother of Cocaine” – it’s not enough to highlight her ambition or troubled background. It’s not even enough to portray her as a loving mother. No. First and foremost, she has to comply with feminine beauty standards.

How utterly reductive and boring.

Miami – multilingual, multicolored, and multiethnic – is different, and thrives on its difference. It is a place where people seek power and glamor, where bodies shimmer on the beach. It is also a place where people go to work and to school, pay bills, and raise families.

It’s not lost on me that Latinas are securing more leading roles in US media than ever before or that Miami is enjoying the spotlight as a thriving minority majority city. But, what images are we seeing? What messages are we sending?

Needless to say, we don’t all look like Sofia Vergara in Miami. We are not all living under the glow of clubs’ neon lights. Hypersexualized Latinas may be common in media, but in reality, we are not inherently pin-up girls. In fact, how we look is often the least interesting thing about us.