There is something inherently off about releasing a film adaptation of Wuthering Heights on Valentine’s Day weekend. In 2026, Warner Bros is packing Emily Brontë’s novel as a tragic romance, but that framing has always been a willful misreading, an attempt to soften a story that is, at its core, about obsession, domination, class resentment, and emotional ruin. In the more than 175 years since the novel’s release, new adaptations promise to unlock its passion. What they often reveal instead is how resistant the actual text is to being romanticized.

Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights leans into provocation from its opening moments, signaling that this will be a bold, sensation-driven interpretation. Fennell is a filmmaker drawn to extremity, and her fascination with desire’s darker edges makes Brontë’s story a logical choice. Boldness is fine – but reshaping a cautionary tale into something closer to a doomed love story is not. Yes, Fennell’s adaptation, like so many before it, misunderstands what makes the novel unsettling in the first place.

When I first read Wuthering Heights in my sophomore-year college English class, I did not come away thinking Heathcliff was misunderstood or tragically romantic. I thought he was frightening. His fixation feels pathological rather than poetic, the kind of obsessive grievance that consumes everyone in its orbit. In a modern context, he’s not a dark romantic hero. He is someone whose behavior raises serious alarm.

And yet, I loved the book. Not because of its love story, but because of its mess. I am a chismosa at heart, and Wuthering Heights is, at its core, a masterwork of gossip. The overheard conversations. The whispered betrayals. The grudges nursed over years. The way characters narrate one another’s worst moments after the fact, reshaping events to justify their own damage. The novel thrives on proximity and judgment. Everyone is watching everyone else, talking behind closed doors as lives quietly unravel. That intimacy, not romance, is what makes the book so compulsively readable.

Brontë’s novel is not interested in love as redemption. It is interested in how desire, once entangled with class anxiety and emotional deprivation, becomes a mechanism of control. Catherine and Heathcliff do not complete one another. They corrode one another. Their bond is not aspirational. It is a closed loop that leaves no room for growth, mercy, or accountability.

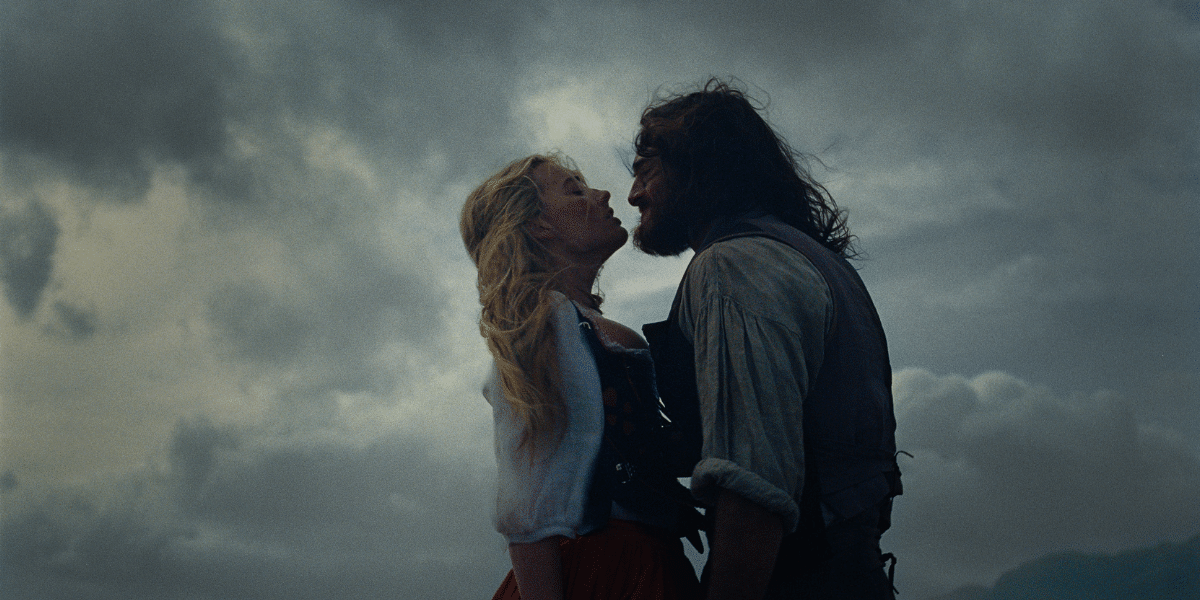

Fennell’s film gestures toward that volatility, but ultimately reframes it as something meant to be felt rather than interrogated. By presenting Catherine and Heathcliff as magnetically doomed lovers, the adaptation invites empathy for a relationship the novel deliberately refuses to justify. Fennell aestheticizes the ugliness that should repel us into intensity. Obsession becomes legible, even seductive, when Brontë’s original power lies in letting it remain unresolved and deeply uncomfortable.

This shift is reinforced by the film’s preference for immediacy. In the film, we’re so close to the bodies, desire, and confrontations. But the book works through distance. The novel unfolds through recollection, rumor, and biased narration. Motives remain murky. We only know some characters through the damage they leave behind. By removing that distance, the film replaces psychological unease with spectacle. The result feels emphatic but oddly contained, dramatic without being destabilizing.

The casting further flattens this complexity. Jacob Elordi is a gifted performer with real range, but he is miscast as Heathcliff. In the novel, Heathcliff’s identity as an outsider, repeatedly described as dark, foreign, and alien, is not incidental. His rage develops within a system that marks him as less than human long before he becomes cruel. Removing that dimension transforms his resentment into something individualized and palatable. What remains is a brooding figure defined by wounded pride rather than a man shaped by sustained exclusion and dehumanization. The character’s menace is softened, and with it, the story’s moral weight.

A different kind of misalignment appears in the casting of Catherine. Margot Robbie is commanding and magnetic, but Catherine is barely sixteen when she makes the decisions that define her life. Her volatility, selfishness, and recklessness are adolescent in a literal sense. Aging her into a fully formed adult changes the stakes. Catherine’s immaturity is essential – her tragedy lies in acting before she understands herself, not in making informed choices she later regrets.

Robbie captures Catherine’s restlessness well, particularly in moments when desire disrupts her sense of control. But the casting reframes Catherine as a tragic heroine rather than a dangerously impulsive girl, smoothing out the moral abrasiveness Brontë insisted on.

The film’s tone mirrors these compromises. It oscillates between seriousness and stylization, between emotional intensity and self-awareness. The effect is less confrontation than hedging, as if the film wants to provoke without fully committing to the discomfort that provocation should bring. The result is visually striking but emotionally diffuse.

That diffusion helps explain the film’s mixed reception. It generates discussion, but little consensus. It is arresting in moments, but rarely lingering. It wants to be experienced viscerally, yet avoids the deeper unease that defines Brontë’s work.

The Valentine’s Day release only sharpens the contradiction. Framed as a romantic film event, this adaptation is courting audiences seeking catharsis and doomed devotion. But Wuthering Heights was never meant to offer either. Brontë did not write a love story. She wrote a warning: about confusing possession for intimacy, fixation for devotion, and suffering for meaning.

Early readers called the novel vulgar and disturbing. Later adaptations tried to civilize it. This film, for all its excess, still pulls its punches, dressing obsession up as passion and offering spectacle where the book offers judgment.

Wuthering Heights does not need to be made sexier or louder. For its story to work on screen, it needs to be hostile, unresolved, and morally abrasive. Catherine and Heathcliff’s relationship is based on the kind of “love” no one should want. And their story is about the damage that follows when we insist on calling their pairing romance anyway.

Nearly two centuries later, that may still be the hardest truth to sit with.