Sujo, an emotionally arresting film by Mexican writers, directors, and producers Astrid Rondero and Fernanda Valadez premiered at the Sundance Film Festival to great acclaim, winning the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic.

“We wanted to do it in the perspective of the child, not in the physical point of view, because the camera’s not always in the real point of view of the child, but in the emotional point of view,” Valadez tells LatinaMedia.Co during the festival in a three-way conversation with Rondero as well. There’s a lot of looking away in Sujo, of letting the action take place in or off the margins of its frame. “As a child, he perceives, he feels, but he doesn’t always see. Sometimes he only hears what’s happening. And that makes sense,” she continues.

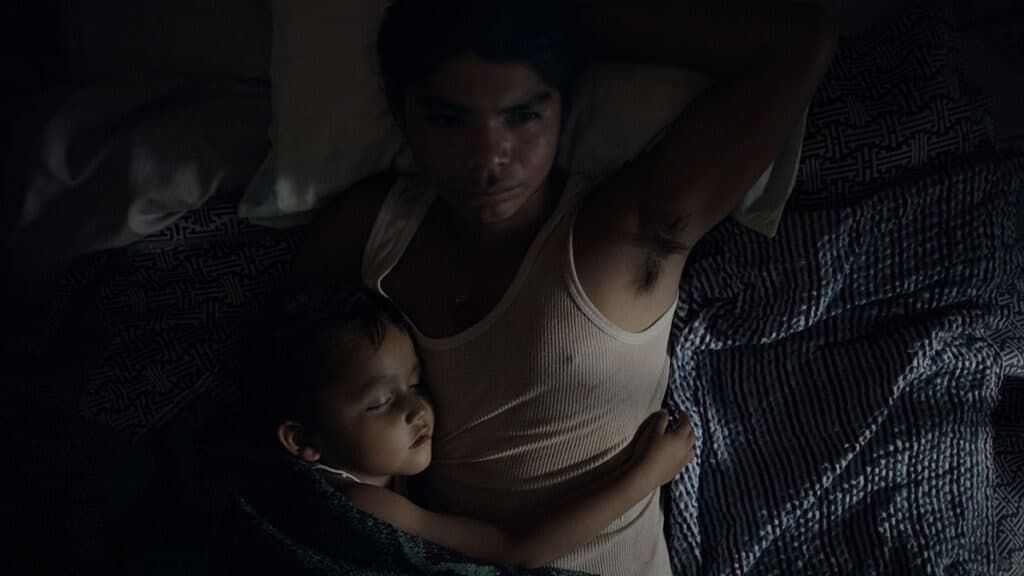

Indeed, their technique makes the voyage of their titular character all the more compelling. Born in rural Michoacán, Sujo is orphaned young, his mother dying in childbirth, and his father murdered thanks to his involvement in the drug trade. The cartel wants four-year-old Sujo dead too, so he’s raised by his aunt Nemesia in isolation. Their only company is his aunt’s friend/lover Rosalia and her two sons, Jeremy and Jai, who are both around Sujo’s age. The film then jumps to Sujo as a teen, who’s become a quiet and perceptive young man, but one on the brink of trouble.

“These kids were very small children – they were inherently good and innocent. There’s something that goes wrong in our country, that a lot of these kids end up being part of this terrible machinery of violence,” Rondero says, explaining how she and Valadez set up the arc of the film. Sujo joins the cartel with his de facto brother Jeremy but then it goes wrong and he must flee again, this time to Mexico City.

And there the camera looks away again, painting Sujo as just another anonymous member of the crowd. “We wanted the viewers to feel how the character feels like he’s trapped and he himself is a symbol of the things that society doesn’t want,” Rondero says, “We also wanted to talk about internal migration, because in Mexico City, we have a lot of people that come from these rural areas that are completely run over by violence.”

It’s devastating to watch our soulful hero so young and yet permanently marked by his country’s failings. In Michoacán, we watched as Jeremy gets his cartel tattoo, a big number 39 on his chest. But it’s not until later, until Sujo is busy in Mexico City trying to turn his life around, that we learn he also has a tattoo. It’s a heart-wrenching moment in a film full of them, even though Valadez asserts they were making the film as “a letter of hope” to Mexico’s young people.

Sujo does not end in tragedy, although it certainly depicts many throughout the film. In the big city, Sujo gets a job and once his immediate needs are met, starts to try to build something more. He finds it at a university and with the literature professor Susan who offers to help him. In that, Sujo is like so many other films you’ve seen – but here the helpful character is no savior. She’s prickly and draws boundaries, even as she’s instrumental to Sujo’s journey.

A lot of the Susan character came from Sandra Lawrence, the actress who played her. Lawrence “is a professor in the National University. She emigrated from Argentina when she herself was a teenager because her family escaped the dictatorship. Some of her family disappeared during that dictatorship. So she herself has this empathy but she’s very clear as [to] her role as an educator,” Valadez tells me after sharing that “people sometimes told us that it was impossible that a kid born in those circumstances [would] be able to relate to someone in city.” But with Lawrence’s real-life example, Valadez and Rondero were able to build a relationship that feels true.

Part of building that truth is making sure the audience understands just how difficult Sujo has it. Arriving in the city isn’t a happily-ever-after for him. The past keeps calling. But that doesn’t mean he’s doomed either. “We felt that it was important to talk about how young men can escape a circle of violence,” Rondero says, asserting how the film is gender specific. In fact, Sujo is the first time the filmmaking duo behind Identifying Features focuses on a male protagonist.

The film itself has a lot of smart things to say about gender – the ways masculinity norms entrap young men and the alternate pathways that women’s leadership offers. It also portrays racial dynamics in Mexico in ways that may feel surprising to gringo audiences that see us all as a brown mass. Sujo, his aunt, and their sisters’ family are all brown and with Indigenous features, while Susan is white and privileged. The cast is phenomenal with strong performances from literally everyone – even four-year-old Sujo (Kevin Aguilar) – a feat Rondero and Valadez accomplished by mixing professional and “natural” actors to much effect. And Juan Jesús Varela as the older Sujo whits the perfect mixture of longing, exploration, and ache. He’s both invisible and the most important thing in the world.

It’s a lot of thought put into this arresting and quiet film. Sujo is most compelling in its assertion of its titular character’s inherent worth. He is a beautiful little boy in the way that all children are beautiful. And something is surely wrong with our society – both that within Mexico and the larger world – that sees his brown body as anything less than.

“We have a debt to young people. We have, I think, a general generational crisis,” Valdez adds, “We have a world that is difficult and violent and aggressive towards young people. And it’s becoming more and more difficult for young people to find the place.” Sujo offers not a map for them but a tribute. It honors them for their youthful innocence and laments their too-often fatal mistakes. Or as Rondero says, “There’s so much beauty in our country, there’s so much. Sujo is this essence of beauty.” And he deserves to be celebrated as such. This film is a start. Now, society just needs to catch up.