I am the eldest daughter of three. Actually, I’m the first daughter, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter on my mother’s side of the family (who we were closer with at the time). For the first few years of my life, I was the star of the show. Every Christmas I’d get more toys and Barbies than I could ever play with. My first steps were a big deal. My first word (agua, according to my father) was something the whole family celebrated and still remembers to this day. I was also the tiny little person in whom everyone deposited their expectations, fears, and hopes of what I would become. I was carrying all that around from the day I was born.

When my sister was born, I went from only daughter to older sister and was suddenly blamed for everything. She started crying? It was my fault for not letting her play with Blas (my huge Easter Bunny stuffed rabbit). Or for not letting her use my Aladdin cup. Or not being gentle enough when I played with her. At three years old, I went from baby to “role model” without really knowing what was going on. I was suddenly scolded instead of praised and it only got worse when my brother was born six years later. Much worse.

Even now that all three of us are adults, I’m still the one expected to “set a good example” and say yes to whatever my parents want, even if it crosses my boundaries. It isn’t just me, though — it’s Latina eldest daughters everywhere. It was my grandmother who had to take care of her brother at a young age. It’s my best friend having to be the scapegoat for whatever her siblings did because “she should’ve been watching them.” It’s even Latinas in films and TV shows that have to carry the weight of everyone’s burdens and expectations and somehow still keep it together.

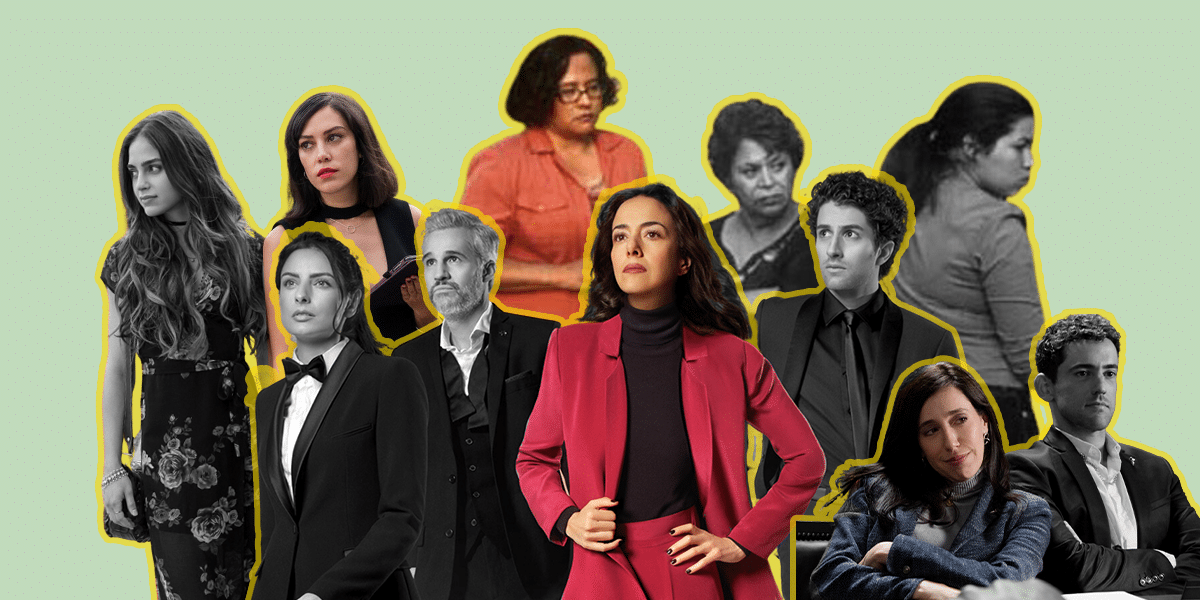

The thing is, if we look closely, our favorite Latinx shows and movies all have that one sister who is forced to push past her own issues to take care of everyone else in her life. The Starz TV show Vida had Emma Hernández (played by Mishel Prada), a type-A queer Latina who is forced to put her successful life on hold when her mother passes away. Her circumstances and the pressure of those around her push her into fixing her mother’s messes (and her younger sister’s, who was always free to be herself and make mistakes). Emma is the one that has to “keep it together,” “be strong for your mamá,” and solve all the problems.

Real Women Have Curves focuses on younger daughter Ana’s (America Ferrera) constant conflict with her mother Carmen. Yet Estela (Ingrid Oliu), Ana’s older sister, is the one who constantly saves the day. Ana needs a job? Estela gets her one at her factory. Carmen is throwing a tantrum? Estela talks her down and makes things right between the family members. While Ana is allowed to pursue her dream and go to college (much to her mother’s dismay, but with her father’s blessing) Estela lets Ana know she was never given that opportunity. She is expected to put her family’s needs before her own. Instead of pursuing her passion, she opens up the factory.

Netflix’s Club de Cuervos is yet another example of eldest daughters not being given enough credit. When it’s time for the Iglesias siblings to take over the family’s soccer club, Chava names himself president o. What’s crazy is that despite his inexperience (and the fact that his older sister Isabel, played by Mariana Treviño, is perfect for the job), most people around him accept this as the natural progression of things. Isabel then finds herself competing for what should have been hers from the start, not because she’s the oldest, but because she was always the one interested in the business. Isabel was the one by her father’s side, learning from him, yet people perceive her as “too neurotic” (sidenote, why are eldest daughters always written as “neurotic, type-A and controlling?!) to handle a first division soccer club.

In La Casa de las Flores, we see Paulina de la Mora (played by Cecilia Suárez) putting her life, her marriage, her relationship with her son, and even her mental health on hold to be her family’s fixer. She’s always running around Mexico City, trying to save the family business, solving her brother’s newest (very public) drama, picking up after her sister’s latest boy toy, calming her mother down from whatever tantrum she’s throwing, or dealing with her father’s secret family when he disappears after her mother’s passing. Every single one of her family’s troubles ends up falling directly on her lap, and whether it was explicitly said or not, she was expected to solve all of it (notice a pattern here?)!

Just like these fictional oldest sisters, I was automatically tasked at birth with being the peacekeeper, the problem-solver, the docile yet independent good example for my younger siblings, as well as being responsible for being a constant source of pride and emotional support for my parents (and oh boy, am I reminded of my faults and shortcomings when I fail to live up to these standards). The emotional weight oldest daughters carry is one that threatens to break us every day. We were the first recipients of our parent’s love, but also their expectations, dreams, hopes, and sometimes even fears (as I write this last part, I couldn’t help but think of conversations I’ve had with friends of mine who are first-gen daughters of immigrants — doubling the pressure in ways I will never fully understand).

The weight we eldest daughters carry has a toll that we never asked for. We deserve some recognition and, to be honest, an apology and a “thank-you” from time to time would be nice, as well. But more than that, we deserve a new narrative where we get to pursue our dreams, make mistakes, and take care of ourselves first for a change.