Child migrants continue to make their way to the US-Mexico border solito. Sadly, political leaders and established immigrant communities continue to take their stories for granted. We’ve become blind to the root causes of migration, which means that even allies with the best of intentions are forced to react to the result of multiple humanitarian crises. Rarely do we create spaces where immigrants of any age can heal or tell their stories from a place of empowerment.

That’s why it matters when someone comes forward.

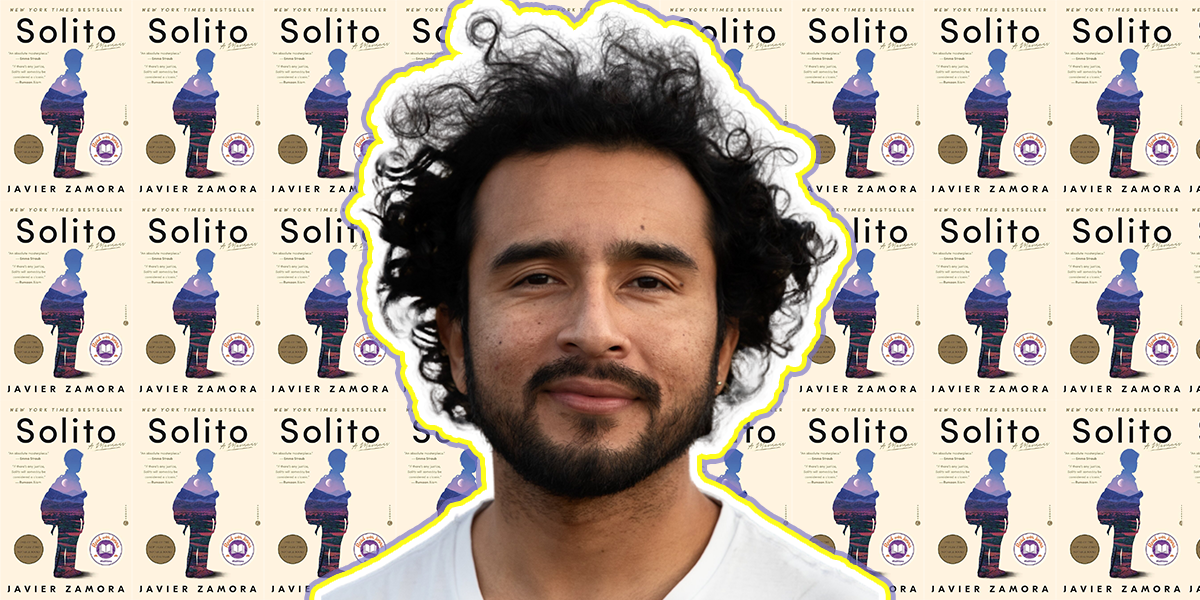

Solito by Javier Zamora was released in 2022. It got a lot of attention from the Salvadoran community, its allies, and fellow writers.

In his memoir, Zamora recalls his journey to the US at the age of 9 in 1999. He starts by giving us slices of his life in San Luis La Herradura, El Salvador. Peppered throughout are recollections about how his parents had already left the country years before he joined them. We meet his family, community, teachers, and classmates and as readers, we too have to let them go as we turn the pages.

The childlike innocence in Solito doesn’t hide the perilous nature of the journey. Once he leaves his neighborhood, Zamora explains how he was surrounded by good people who became his de-facto family as they crossed. His observations of people he met, places he traveled to, coyotes (smugglers), and authorities are imbued with the wisdom of a kid who was forced to grow quickly because of this necessary “trip,” as he calls it. In multiple instances in Solito, Zamora explores the kindnesses he experienced in Guatemala and Mexico.

The best writing is specific and unafraid. As a Salvadoran-American, I and other diaspora Salvis have recalled how often we were teased or discouraged from using caliche (aka Salvadoran slang) as children. I expressly remember elders in the family explaining that if I speak that way, other Latinx communities might see me as less than. But Zamora sprinkled in multiple Salvadoran terms throughout the book, adding to the essence of Solito. Seeing these words on a printed page and treated with respect was meaningful to me as I’m sure it was to other Salvi readers.

I can’t speak for everyone, but it’s common for many Salvadorans to shy away from talking about traumatic subjects – the Civil War, family hardships, or tough childhoods. Stories about migration can be especially harrowing for our elders to discuss, even if they were lucky to arrive on planes or qualified for green cards. I was often told it was rude to ask questions and that recollecting is a step backward. We moved to the US to move forward, they told me. But Zamora didn’t let that stop him as I read when he explains his process at the very end of the book. He opens up about conversations with his family, some of whom later made it to the US. That couldn’t have been easy, and I’m glad he was able to have the conversations many of us can’t.

Solito might be triggering, but it’s a great read if you too have relatives who aren’t ready to open up about their immigration story. Not all of us will be able to get our answers, especially when there’s still so much shame in our culture as it pertains to experiencing trauma. What we can do is support those who can share their journey. If you haven’t had the chance to read Solito yet, it’s available at bookstores nationwide.