I’ve always thought of Colorado as a white place. Despite the Spanish-language name, the state has marketed itself as more like Kansas than New Mexico and it’s worked. I mean, my dad is a professor of Chicana/Chicano studies and I grew up steeped in Mexican American history, learning the ways we are erased and the consequences of that erasure. Having lived in all four border states (CA, AZ, NM, and TX), I’ve noted the differences between how Latinx culture is presented, perceived and lived. So if anyone should have questioned the white narrative of Colorado, it was me. But I didn’t — I fell for the whitewashed marketing of the state, never doubting my impression that Colorado is and has been gringolandia.

Fajardo-Anstine captures the empty, arid, barrenness of the desert, contrasting it with the book’s other settings and filling the silence with real people — your primas and tias and amigas, dealing with things you wish they didn’t have to.

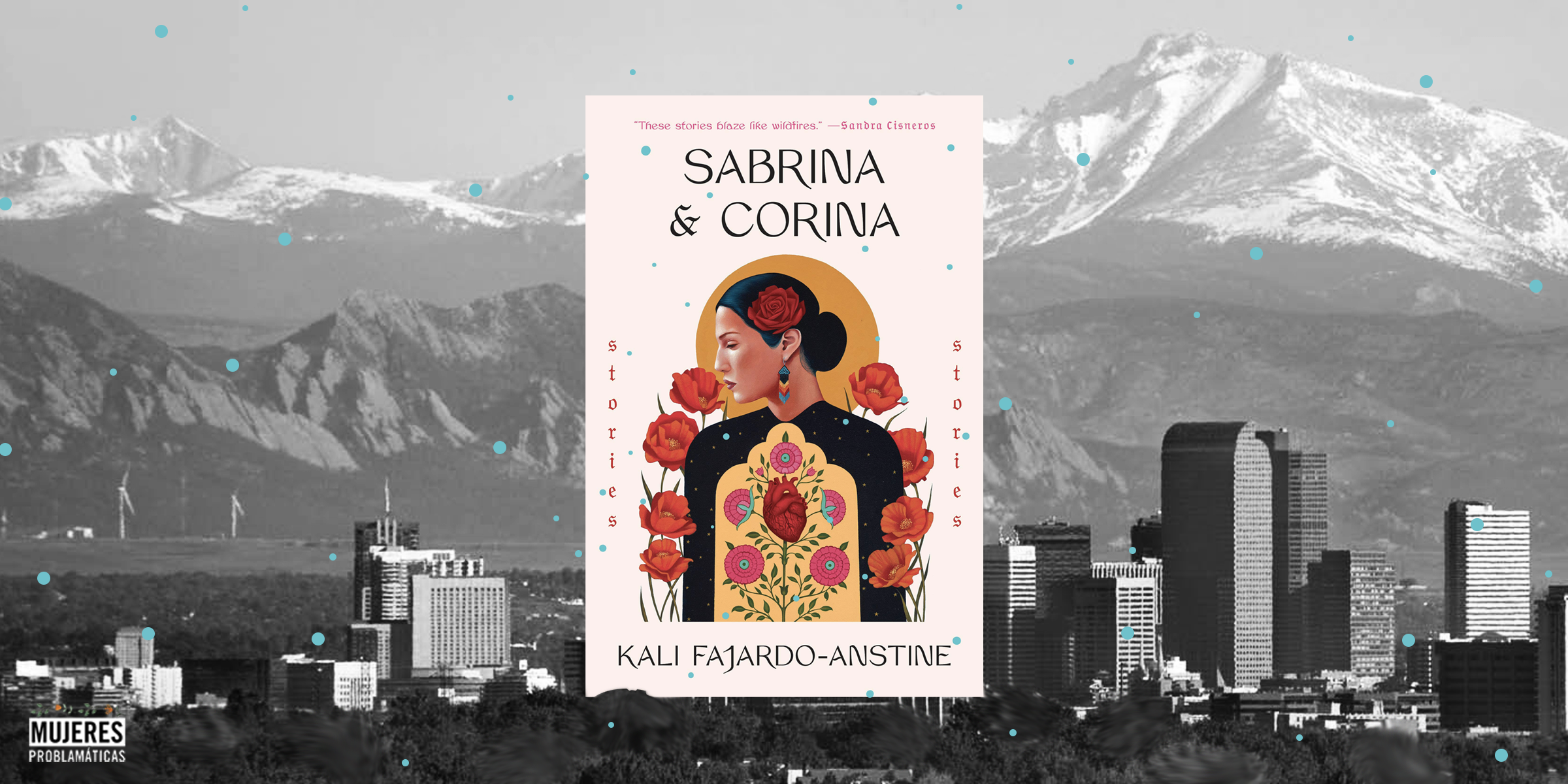

That is until I read Sabrina & Corina. Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s debut book is a collection of stories each centering a Latina protagonist from Denver. The stories span decades, revealing different facets of Colorado’s history with rich and beautiful writing. Fajardo-Anstine captures the empty, arid, barrenness of the desert, contrasting it with the book’s other settings and filling the silence with real people — your primas and tias and amigas, dealing with things you wish they didn’t have to. Each story keeps you turning pages as it breaks your heart with accounts of gender-based violence, bad-parents kept and good parents lost, and the psychological effect of your history, identity, and family being systematically erased.

Sabrina & Corina explores these pressing issues with nuance and compassion. Take the treatment of sexuality: in the title story, we see two cousins, one uncannily beautiful and “fast” and another responsible, conservative, and normal looking. The beautiful one trades on her looks for quick escapes, relying on men for her sense of self and her economic day-to-day. She ends up murdered by one of her partners. The other avoids men, relationships, and sex, living alone and isolated, even losing touch with her favorite cousin. Neither is a good choice.

On the other end of the spectrum, we see Alicia in “All Her Names” use her sexuality to literally ensure her freedom, pretending to be mid-tryst to escape the cops after tagging a train car. And this serves as background for a character who has an abortion without telling her husband and spends the majority of her narrative with her sometimes-lover, reliving what it was to be young and reckless. Sexuality is complicated and Sabrina & Corinadoesn’t back away from that as it portrays the lived experiences of Coloradian Latinas.

Sexuality is complicated and Sabrina & Corinadoesn’t back away from that as it portrays the lived experiences of Coloradian Latinas.

Likewise, Farjado-Anstine’s debut captures what it feels like to be the object of gentrification. In “Galapago,” we see a middle-aged woman try to convince her grandmother to move out of the old neighborhood. She remembers the break-ins over her grandmother’s 60+ years in that house and the ways in which the family contorted themselves and their home to continue thriving despite the surrounding violence. That story ends and begins with the grandmother Pearla killing a nineteen-year-old intruder — it’s finally time to move out.

In the last story, “Ghost Sickness,” we see the gentrification of history, not just houses. Here our protagonist Ana is a college student in danger of flunking History of the American West. She just can’t merge what she knows of the area — what the events described in her textbook felt like from the indigenous perspective — to the White Man’s version of explorers, tamed wilderness, and manifest destiny. She’s also dealing with the disappearance and probable death of her live-in boyfriend. This story ends with a modicum of hope — Ana may just pass the class thanks to an extra credit question on the Navajo original story, something she knows in her bones thanks to that missing, Navajo lover.

Overall, Sabrina & Corina made me feel seen, silly, and sad. Seen because these women are women I know, women I’ve been, but women I so rarely get to see portrayed. The power of centering Latina’s perspectives cannot be overstated. I also feel silly for knowing so little about my sisters in Colorado — I mean, I didn’t even know they existed! This erasure isolates us, keeping us from knowing and working together. And lastly, I was sad. These stories are heartbreaking and make you feel for each heroine as she deals with the tragedy before her.

Our experiences are not your sadness porn. There is in fact great beauty, humor, and strength in being Latina.

I hope Kali Fajardo-Anstine writes and publishes many more books. Her voice is powerful and her focus on women of color needed. But scrolling through reviews of Sabrina & Corina, I was uncomfortable by all the white women praising it, not understanding that to be Latina is not just to be in pain or doomed to tragic circumstances. Our experiences are not your sadness porn. There is in fact great beauty, humor, and strength in being Latina. And I hope Kali Fajardo-Anstine uses her considerable talent and now thankfully-large platform to share the joy of our identity with the world too. With so much sadness, we need the moments of joy as well.