South America has a long history with telenovelas and Brazil is no different. Going all the way back to the 19th-century newspaper serial, evolving to radio dramas, and culminating in the telenovelas we know today, this media genre has been key in shaping how we think about our political and social spheres including queer people.

Of course, that wasn’t always the case. In their early years, telenovelas were much more inclined to tell tales of foreign lands and exotic heroines. Perhaps, it was because they have 19th-century French origins. These novelas were serial publications that came around 1836, when the newspaper La Presse was worried about the drop in sales of their publication. To combat that, they started to print famous stories written by Dumas, Victor Hugo, etc., that would always end in a cliffhanger, urging the reader to buy the next publication.

Another factor could be the two separate dictatorships Brazil went through, one led by President Getulio Vargas (1937-1945) and a second known as the Military Dictatorship (1964-1985). While under these regimes, the government censored Brazilian media companies so they couldn’t discuss topics considered controversial, like labor laws, women’s rights, and, of course, LGBTQIA+ people.

But like in any society, that only worked to an extent. From the 1960s onwards, tales of damsels in distress fell out of fashion, and naturalistic stories began to populate our screens.

Influenced by the Tropicalia and the Cinema Novo movements, telenovelas adopted a language that was more focused on the average person, their struggles and desires. And that included queer people.

The first instance we have of a telenovela – or rather a teletheater, which is a theater play performed for a live audience and broadcast live on TV – representing a queer person is O Caso Maurizius (1960) where the characters of Waremme (Sergio Britto) and Etzel (Claudio Cavalcante) share a quick kiss.

That was progressive for the time, but these characters were far from the representation the queer community wanted. The more openly gay, Waremme is the typical sleazy stereotype, with a propensity for evil plotting and seducing innocent young men, such as Etzel.

And while media is not the sole reason why people think the way they do, it is undeniable that being exposed to certain patterns can influence how we feel and behave towards a group of people. For instance, a study by the National Hispanic Media Coalition (NHMC) shows that people who receive positive messages regarding Latinos, regardless of where that messaging came from (news, commercials, telenovelas, etc.), have a more positive perspective of the group.

That is also true for the LGBTQIA+ community. Renan Quinalha, professor of Law at Unifesp (Universidade Federal de São Paulo), lawyer, and human rights activist, explains that for the Brazilian audience, specifically, telenovelas are key factors in educating straight people about the queer experience.

However, Quinalha warns that the mere presence of LGBTQIA+ characters in telenovelas is not enough. After all, these same shows are quick to perpetuate stereotypes. The two most common being the cisgender, white, effeminate/comic-relief gay or the asexual/often-closeted gay.

Neither characters are inherently wrong. But the fact that these were the only possible storylines for queer characters from the 1960s all the way to the 2010s, created a limited understanding of the Brazilian queer experience.

Of course, there were attempts to explore more complex characters, but often they either fell back into stereotypes, got slowly pushed away from the main storyline, or, in more extreme instances, suffered the Bury Your Gays treatment. The most famous example is the tragic fate of Leila Sampaio (Sílvia Pfeifer) and Rafaela Katz (Christiane Torloni) from Torre de Babel (1998), who got murdered in an explosion due to audience pressure (aka homophobia) to get rid of the couple.

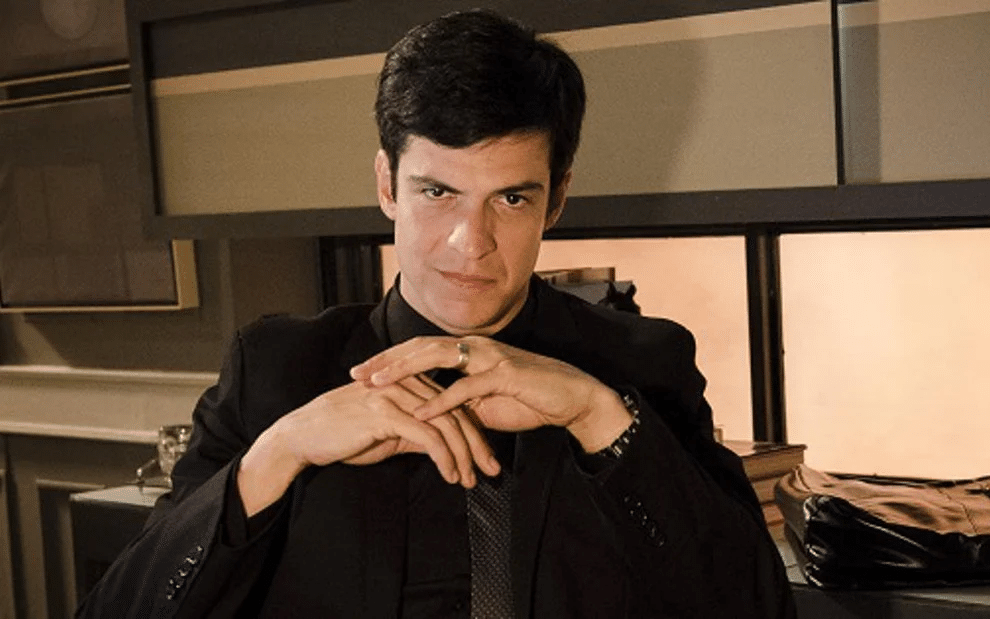

It was only through the work of LGBTQIA+ activists and telenovela writers – many queer themselves – that change started, the biggest shift happening in 2013 with Félix (Matheus Solano) from Amor à Vida. Written by Walcyr Carrasco, an openly bisexual telenovela writer, the character of Félix begins the narrative as the stereotypical villainous effeminate/comic relief gay. He kidnaps and throws his newborn niece in a trash can, moves in an exaggerated way, and communicates with funny catchphrases.

However, as the chapters roll out, something changes. People liked Félix, but not in a funny, gay-friend way. Solano’s performance may have humorous, but people began to empathize with Félix as a person. First, audiences related to Félix’s troubled home life. A father that clearly favored his sister and refused to allow him to participate in the family business.

Suddenly, Félix was no longer the evil scapegoat. The complexities of the writing, along with Matheu Solano’s performance, truly captivated audiences, and the show went on to give Félix a redemption arc, becoming one of the first queer characters to lead a telenovela in Brazil.

The final episode culminates with Félix caring for his elderly father – who asks for forgiveness and tells his son he loves him – managing the family business, and kissing the love of his life, Niko (Thiago Fragoso).

While Félix’s journey was a turning point for queer representation in Brazilian telenovelas, it was far from the end goal. After Amor à Vida wrapped, there have been many LGBTQIA+ characters on television and not all were as rich as Félix.

Doctor of Human Sciences and Gender Studies at UFSC (Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina) and journalist Fernanda Nascimento explains that you can not expect that after one successful part, all others will follow suit. To her, these characters are a reflection of the advances and setbacks of our society.

Regardless, Nascimento emphasizes the importance of these characters existing at all. To many viewers of telenovelas, these characters are their first, if not only, direct contact with the queer experience. So these storylines are key in shaping how our society views LGBTIQIA+ people. It is undeniable that there is still a long way to go. Many stereotypes continue to persist for telenovela’s queer characters. However, it is worth celebrating the journey that’s gotten us to today. From early depictions of sleazy gay men in the 1960s to the 2024 cast of Renascer, where a trans woman and a lesbian occupy leading roles, we’ve come a long way!