Pedro Prensa wakes up and measures the width of his head against a wall. He wants to know how much further he needs to squeeze it. Then, he takes a wrench and tightens the press around his head, squashing his bones. He repeats this act of self-torture day, after day, after day. This is the trigger of La otra forma (The Other Shape), screening at Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival (LALIFF) this weekend. This new wordless, animated film by the Colombian director Diego Felipe Guzmán challenges how we tell stories.

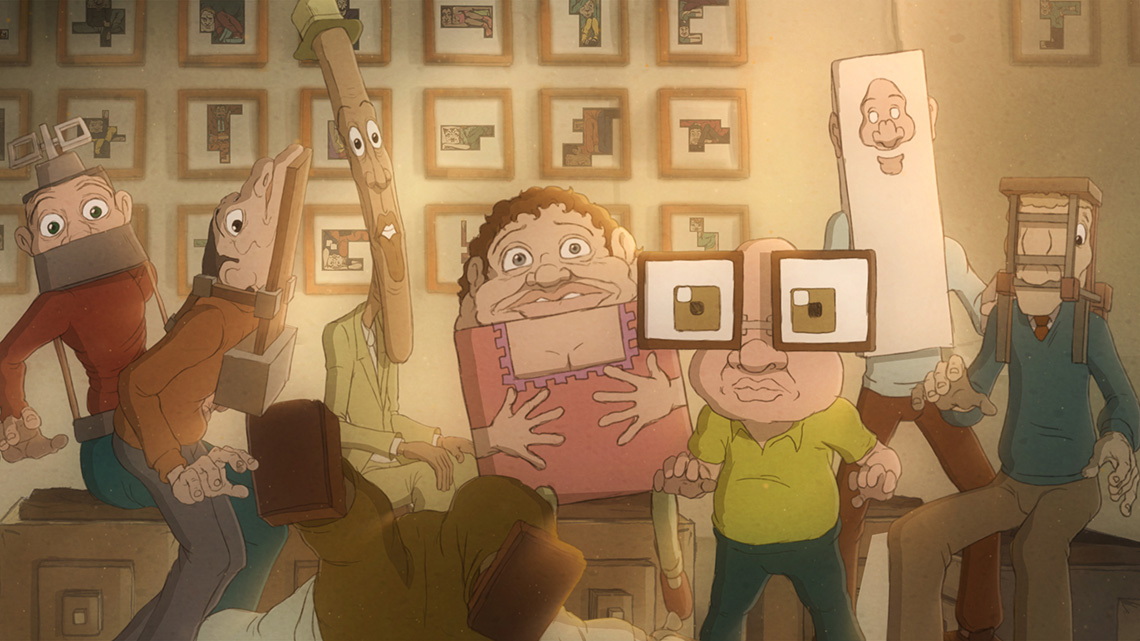

As we begin to see the world Pedro Prensa inhabits, we learn this strange behavior is not exclusively his but generalized in the entire population. Everyone on this planet is focused on modifying their bodies in whatever way they can to make them fit inside a square. Whether it is stretching the skin in their faces until they can cover a frame with it, fitting their bodies into a zigzag, or flattening their skulls until they look more like toads than humans, everyone is modifying themselves to make them fit into an unnatural ideal.

Their ultimate goal is to earn a spot in a gigantic puzzle on the Moon’s surface, a sterile paradise around which everyone’s existence evolves. As you would expect, all the pieces fall nicely into place until two forces appear in play: curiosity – seen as Pedro’s questioning of why things have to be that way – and a fluid force that could be Nature or the Wild Side of the psyche, as the Jungian psychoanalyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés would call it.

La otra forma is a Colombian movie without any mention of violence or the Colombian armed conflict. Even more, it is a Colombian movie that dared to dream of a context that cannot be tracked to any particular country or culture, and yet, we can all relate to its central conflict: being forced to fit somewhere alien.

The choice of making a silent film reinforces its lack of cultural specificity: the characters make certain noises (like panting, for example), but they don’t talk. However, it has the downside of making the movie feel too long towards the end as the series of events that break with the status quo repeat themselves for several minutes, which makes it hard to keep the audience’s attention.

The other point worth noting about La otra forma is the monumental amount of work that was put into it due to its technique: frame-by-frame animation. Creating its one hundred and fifty characters (of which only five are central to the story) required a hundred artists, five years of work, and a colossal number of 60,480 drawings with a budget of about half a million US dollars. The fact that Diego Felipe Guzmán and his team managed to create such a film, under those circumstances, is proof of their tenacity. But that doesn’t mean artists should work without resources, led by the force of their passion. In fact, it’s more like the opposite – let’s hope that La otra forma helps to create more grants and inspires more companies to invest in the Colombian film industry.

La otra forma deserves credit for doing something radically different from what has been the trend of Colombian movies during the past decades and taking the animation technique to a league Colombian cinema had not explored before. Perhaps one of the signs of a society healing from its violent past (and present) is when it dares to dream differently, and here we are in the face of another kind of imagination, questions, and ideals.