On the surface, La Guagua Aérea (A Flight of Hope) presents as a classic story about [e]migration – one where nostalgia and necessity join in search of a new life in América. But the 1993 Puerto Rican dramedy delves deeper, reminding us that leaving one’s country often creates issues with identity, cultural pride, and assimilation.

Set against the backdrop of a midnight 1960 Christmas flight to New York City, we follow the journeys of 10 passengers, some of whom are leaving their beloved Isla del Encanto for the first time. What ensues is a deep look into ourselves, both as a people and as a classist society.

Right from the beginning of the film, director Luis Molina Casanova gives us a peek at the metaphorical mirror he’s constructing when we hear the narrator’s serious voice juxtaposed against the excitement at a crowded Isla Verde airport. “I’ll never forget that December 20, 1960. The airport was jam packed with travelers awaiting the midnight flight, when fares were cheapest. They were going to [find] work, heading for a different life in the promised land, those people were looking for a new hope. But me, I was going to meet a new país – not in New York City – but my own country on the airplane.”

Set in an era when there was much less security and more lenient policies regarding carryon items, La Guagua Aérea makes us laugh at the chaos it presents on the screen: an entire family of eight dropping off one relative at the airport, the long queue of passengers carrying all manner of things (a circular hat container, brown boxes filled with homemade arroz con gandules, an oversized blanket). But behind the holiday merriment lies what many of us sense – the pain of knowing that some of these passengers will never return to their Borikén.

One father dropping off his college-aged son tells him, “Don’t be discouraged son. Before you know it, you’re going to be living like a king over there.” Those words neither assuage his son’s grief nor ours as we contemplate the struggles many will face on the other side of the Atlantic.

It is this sentiment that is echoed at various times during the movie. Again, at the opening airport scene, we meet an elderly man, Don Faustino Román (played by José Luis ‘Chavito’ Marrero who turns out to be the narrator). He is going to New York City expecting to bring back his son, Israelito, who went to find work a few years earlier and never returned. When his worried granddaughter asks “¿Abuelo tú vas a volver?,” he reassuringly tells her he will but we’re left doubting it.

Later on, we watch a flashback where Don Faustino tries to convince his son not to leave their countryside home. The son, who is about to get in a pickup truck to the airport, replies, “Papi, I’ll be back once I’ve earned plenty of money in New York to pay off the debt owed on our house.” We hear the angst in the man’s voice as he reminds his son that “aquí en Puerto Rico, there’s also work.”

In addition to the obvious emotional attachment Don Faustino has for his son, his regret is palpable. It brings us to the theme of leaving one’s homeland for economic reasons while navigating the tension between cultural pride and assimilation.

We see this blatantly in the character of Orlando Colón (Ángel F. Rivera), an arrogant Puerto Rican businessman who frequently travels between the archipelago and New York City. Mostly speaking in Spanglish, his voice drips with disdain as he engages a taxista in conversation, offering to hire him as a driver to take him to tour Park Avenue and then to Rockefeller Center so he can go ice skating. Colón berates Puerto Ricans who live in New York City, saying they, like his cousin in the Bronx, “Always want to stick together and never do anything to get ahead.” At that point, the taxista tells Colón, lover of all things gringo, about how the taxista spent three years working in a factory, scrapping bottle labels until his fingernails were raw. He shares how he worked in a laundromat for two years, but was fired the minute he asked for a raise.

In another scene, we find Colón complaining to the flight attendants about a group of passengers congregating in the back of the airplane, with a guitar and a guiro singing Puerto Rican Christmas tunes. He indignantly says, “It’s like a jungle out there,” later adding, “I cannot believe these people, sometimes it makes me ashamed that I am Puerto Rican.” He’s an example of the sell-out, the one who’s embrace of Gringolandia has made him hate his culture and thus, at least a part of himself.

La Guagua Aérea functions as socio-economic and political commentary, using its reminiscences from la matria of Borikén to make a point about who gets to stay home and who has to leave. For example, we meet a young mother, Pilar Marrero (played by Alba Nydia Díaz) with a festive holiday chorus playing in the background. She’s in conversation with a fellow passenger telling her, he would request a few Cortijo [salsa] records if someone asked him what he wanted them to bring him from Puerto Rico. Somberly, she looks at him and says, “I would’ve asked them to bring me a star-filled sky.” Shocked, the man asks, “Aren’t there any stars in New York?” “No, if there were, I would’ve seen them,” she says and her yearning for her home flows from her lips to our ears.

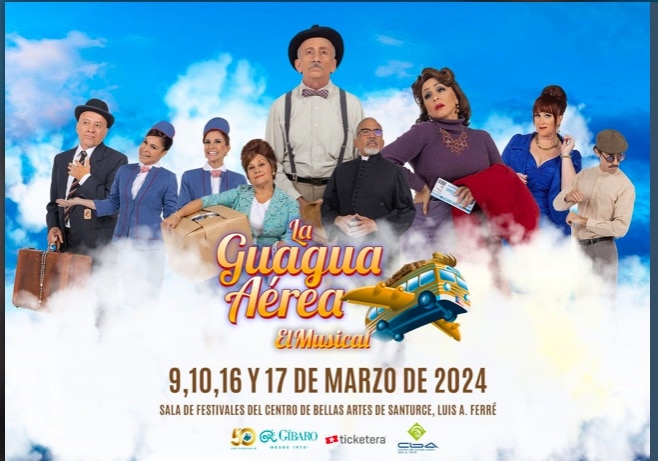

Thirty years since the film’s release (and having first debuted on the theatrical musical stage in 2022), the piece has once again landed in the mouths and on the minds of countless Puerto Ricans. This upcoming March, the play returns as a musical production to the Sala de Festivales del Centro de Bellas Artes de Santurce, San Juan. My hope is that it will inspire a reverse emigration – like mine – where many displaced puertorriqueñes return to this ancestral motherland.

You can catch La Guagua Aérea in its original Spanish on YouTube.