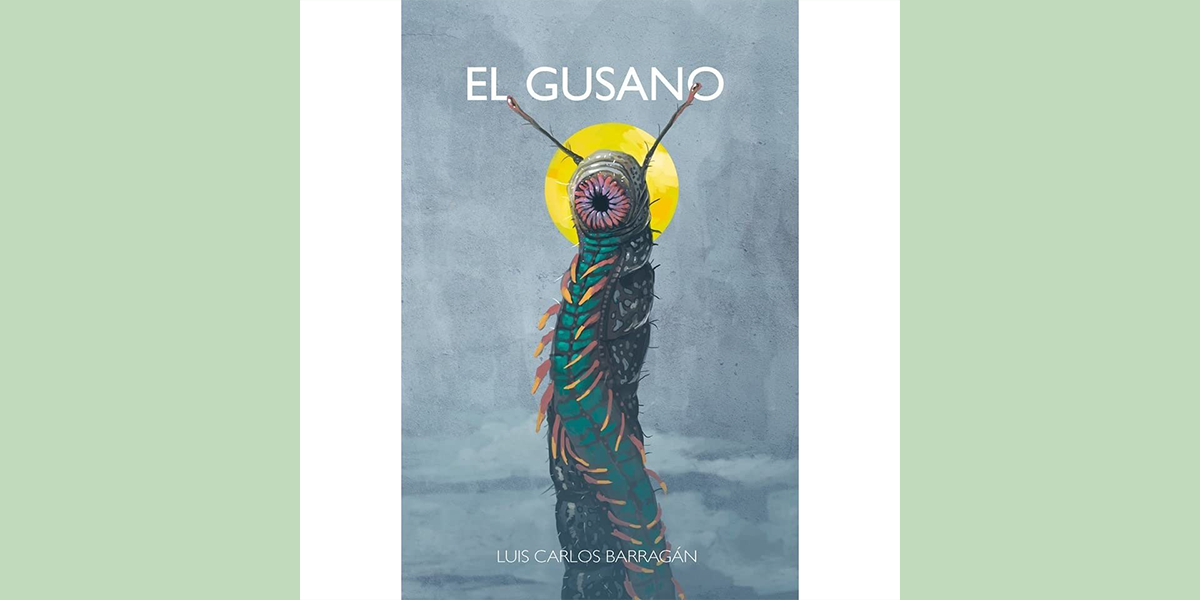

El Gusano (The Worm) is a science-fiction book where bodies have no limits and can merge, mix, and combine endlessly. It starts in 1997 and radically changes life on Earth. People begin feeling afraid of touching each other, and they walk around completely obscured in clothing, covering their faces and hands, avoiding contact at all cost (It does ring a bell, right?). But that possibility also sparks new forms of loving, playing, partying, and even killing and disappearing.

This is Luis Carlos Barragán Castro’s second novel, after the surreal Vagabunda Bogotá. With El Gusano, Barragán Castro shows a trend in his work, where he integrates the imaginative power of science-fiction and the richness of Latin American culture to imagine better worlds. Not perfect, not absent of conflict, pain, confusion, or death, but better.

El Gusano starts with Cesar, the book’s main character, merging his body with a Syrian girl, Sarah, when they are both six years old. From there on, he lives with a tiny new vulva and she lives with a tiny new penis. They also exchange hair and eye colors, the languages they speak, and some particular tastes. The book then follows Cesar on a journey through the Colombian armed conflict, the Syrian war, Donald Trump’s presidency, the creation of a new kind of sex toy, a sect in the jungle – you name it.

El Gusano takes its premise to the last consequences to ask whether a better though stranger world is possible… It offers a glimpse into a place where we wouldn’t be able to discriminate against each other based on race, sex, money, or cultural reasons. One where we would understand that there is no such thing as “the other.”

This is a conversation with the author.

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: Do you remember the first idea of what would become El Gusano?

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: A few years ago, I was living in Egypt and I was very lonely there. I had a partner, but our relationship was falling apart and, somehow, what made me think about this was hugging someone and feeling that a hug was not enough. I don’t know if you have ever felt something like this… it is when a couple wants to be together but, more than together… they wish to merge.

So that was the birth of it. Then I mixed that with Evangelion, the Japanese anime. There is a scene in the movie where a character gets his hand into Rei’s chest. That gesture of getting your hand inside of someone, as if the body had no limits, was what sparked the story, the idea of what could happen if people could do it and it were normal.

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: Many kinds of diversity intersect in the novel: cultural, physical, sexual diversity, etc. How do you see the relation between them, and how was the process of working through them in the novel?

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: One of the problems I reflected on the most when I began working on the novel was people’s incapacity to communicate with one another. At first, I thought about it in regards to couples, but then I began thinking about the way many violent events in history are related to that.

For example, I have been robbed several times here in Bogotá; and I always felt that if the thief could feel what I was feeling, he would be so terrified that he would be incapable of robbing me. Because, in order to assault me, he would have to do it to himself first. That was one of the ideas I had in mind.

And the point is that if people could merge, they wouldn’t just join; they would feel the other person. And that would make impossible many kinds of violence. And not just of direct violence, but differentiation and any sort of discrimination would be impossible too. Because, if the other is you, how can you discriminate against them without discriminating yourself?

I think I began imagining the solution to several problems. At first, I was thinking from Colombia and Latin America, how this could affect our problems. But then, I went far beyond, to the Middle East, and most of the issues regarding wars, conflicts among social classes, and how they relate to those identities.

Identities intersect with privileges, and I thought the possibility of merging, of feeling the other, could flatten those conflicts. I would it would be amazing to fix the world’s problems.

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: But that way of merging also made possible new fears that can only appear if you may become someone else.

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: I guess you are thinking of, for example, when people can’t touch each other, or they could, but they don’t want to. They could understand each other perfectly. It is the best way to solve the world’s problems, but they become worse. Because people are afraid of being “the other,” fearful of being Black, Venezuelan, woman, Afghan, you name it. And so, they isolate even more. Eventually, they could force each other to merge; actually, it happens in the novel.

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: There seem to be three kinds of fear in the novel: the fear of assuming who you are, the fear of identifying in someone else, and the fear of not knowing any longer who you are because of how many times you have merged with other people.

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: Exactly. I think it is a fear we face in everyday life, not only in El Gusano. It is a fear of being something we don’t want to be or accepting we don’t like who we are.

For instance, in the novel, there are paramilitary forces of people who don’t want to have parts of people they don’t like or that make them suffer. Because when two people merge and split apart, they begin feeling a very intense longing for each other. An insufferable kind of nostalgia. There is a metaphor to that idea we have been sold that we have to be independent, that we can’t depend on each other and have to be self-sufficient to avoid weakness. That kind of culture turns us into isolated, egotistical people. In the book, that fear leads to the creation of an extermination group: they kill the people with whom they have merged simply because they are incapable of accepting that kind of union.

It could be a metaphor for paramilitarism, homophobia, fascism, or the idea of wanting to be pure one way or another. It is a metaphor for the idea that some are stronger or better than others. It is all mixed with those fears.

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: Science fiction has many ways of speaking about the real world, but in the case of El Gusano, it is interesting how you made the premise fit in the contemporary world. How was the process of making that happen?

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: It was a very planned thing. I included two conflicts in the novel: the war in Syria and the peace process in Colombia, which was going on when I wrote the book. Also, by that time, Donald Trump was elected as president.

There is something I took a bit lightly, and it is that I made that change in the world’s history since 1997. If people had begun merging that year, the world we have nowadays would be totally different. Most likely, Donald Trump would not have made it to the White House, and many other things wouldn’t have happened. But I felt it was okay to fit some events of our world into that alternative one.

The process was very organic. For example, I thought I could use my idea of the fusions to explain the armed conflict in Colombia. I love the idea that the people who make things happen in a war, those with the money and the power, could feel what they are causing. That they could feel in a single blast the pain of those who lost their homes, their families… because those are consequences that powerful people can’t measure. I was thinking about all of that while I was writing the book.

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: Is there anything, in particular, you feel El Gusano could teach an American audience?

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: I feel it fits like a glove to them. Because in the US, the identity crisis is constant, and everybody is labeled: Latino, Black, Asian, White. And each one of those labels includes a conflict: being a woman, gay, Muslim. All those labels are so apart from each other that I think it would be a powerful thing if fusion were possible. Or at least, it would be exciting to imagine how those identities could mix in a blender and dilute separations.

I am not saying that we should end them. The richness of humankind resides in its diversity. But I think in the US, it is very evident how that struggle for identity, for being acknowledged, not only named by white men, is a constant struggle, and the chance of tearing down those limits is a beautiful idea.

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: What is next for you?

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: My next novel, Tierra Contrafuturo, is out for sale. Minotauro published it, which is the biggest science fiction publishing house in Spanish (they have the publishing rights of people such as Ray Bradbury in Spanish.)

It is a novel in which Colombia makes contact with a group of aliens that arrived in the Vaupés (a South East part of the country). And a person makes a deal with the aliens to make an interplanetary embassy, right where there crashed because an interdimensional gate was opened.

And so, the Colombians win a development scholarship for poor planets (such as Earth), and other planets give support for education, technology, and development. With that scholarship comes a bunch of technologies, aliens coming to teach and study Earth History, and it opens up the possibility for people to go to other planets.

What happens, finally, is that Colombia and, particularly, Mitú, becomes the center of the Earth, and a Golden Age starts, although it brings several threats along with it. The idea is to imagine Colombia as the center of the technological and scientific move…

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: And geopolitical, as well.

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: Yes. More because of an accident than because of us. (Laughter)

ANA MARÍA ENCISO NOGUERA: The corruption would tear us apart…

LUIS CARLOS BARRAGÁN CASTRO: Indeed. Corruption is the biggest problem of all Colombians (laughter), but that is how it goes.

Lately, I want to think from a place of optimism: we have many problems and all we see in the news is negative up to the point where it seems to be impossible to imagine a good ending to all of this. I think science fiction allows us, at least from a symbolic perspective, to heal those wounds and imagine alternative ways, even if they are pure fantasy. Science fiction allows us to imagine it doesn’t have to be that way.

Science fiction has been traditionally very pessimistic: lots of dystopias, post-apocalyptic stories where everything goes wrong or where machines take control of everything… so I like imaging things differently.

El Gusano is available at Ediciones Vestigio and Storytel as an audiobook. Tierra Contrafuturo is available at Planeta de Libros in eBook format.