Bad Bunny’s DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOTos (DtMF) is more than just a short film; it’s a visual poem, a lyrical meditation on memory, loss, and the ache of impermanence. As a visual artist who thrives on discovering hidden layers in works of art, I can’t help but view this piece as a testament to his evolving artistry. Bad Bunny has long mastered the art of emotional storytelling through music, but here, he steps into a new realm – one where images, silences, and fleeting moments carry as much weight as a beat drop.

Watching DtMF, I couldn’t shake the feeling that this isn’t just a film. It’s an invitation. An invitation to linger, to feel, to find the Easter eggs tucked into every frame. Where a photograph not taken becomes a symbol for missed opportunities, for the moments we fail to appreciate until they’re gone.

But this isn’t just about nostalgia or regret; it’s about artistry. Bad Bunny, who wrote and directed the short, approaches filmmaking like a poet, selecting each shot and detail with intention. The frames are layered – there’s always something happening in the periphery, a reflection in a window, a fleeting glance, a shadow that tells its own story. His attention to detail elevates the work to visual poetry.

I found myself excitedly pausing to catch the subtleties: a lingering shot of a clear Borikén sky, the rich soil underfoot, a cafetera percolating. These moments felt deeply personal, as though Benito was allowing us to leaf through his journal. And isn’t that what poetry is at its core? A distillation of emotions too complex to say outright, presented in a form that invites interpretation and connection.

One of the film’s most poignant elements is how it collides the gentrification of Puerto Rico with the aging of a man. We see a life marked by missed moments and the inevitable forward march of change. This duality – personal and collective – hits hard. The erosion of memory mirrors the erosion of land, culture, and identity. The film asks a devastatingly simple but profound question: How do we restore what’s been taken?

The parallels are striking. The gentrification of Puerto Rico isn’t just a loss of land – it’s a loss of self, a displacement that feels deeply personal to those who call the archipelago home. Similarly, the man in the film reflects on the life he’s lived, the things he’s missed, and the irreversible tide of time. Change, the film suggests, is inevitable – but not all change is progress. Some change damages. Some change erases.

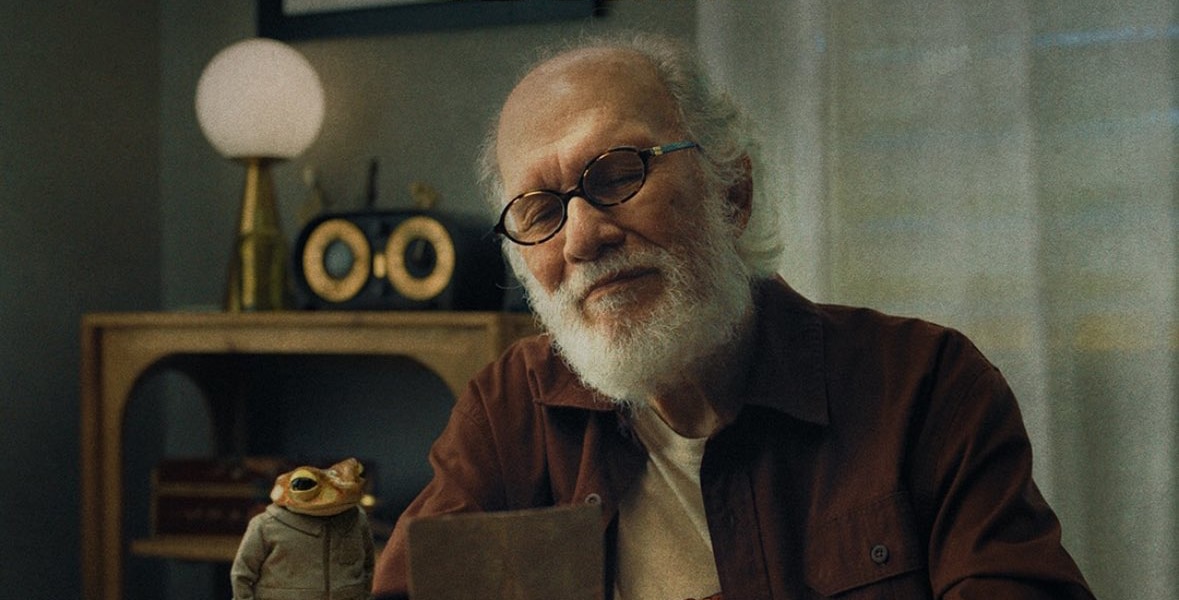

The concho, an endangered Puerto Rican toad, becomes a poignant metaphor for the fragility of what is easily overlooked or forgotten. His presence in the film mirrors the precarious state of Puerto Rico itself grappling with the forces of cultural extermination, challenging us to confront not only what has been lost but what still remains – endangered yet enduring, waiting to be protected and reclaimed.

Yet DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOTos doesn’t offer simple answers. Instead, it invites us to sit with the discomfort of these questions. How do we go back? Can we go back? For Puerto Rico, where the impacts of colonization now morph into the violence of gentrification, this question feels especially urgent. The archipelago’s natural beauty and cultural vibrancy are being packaged and sold, more often than not, at the expense of our people.

Bad Bunny has been vocal about these issues in his music, in his previous documentary/music video El Apagón – Aquí Vive Gente, and here, the same concerns echo. And yet, the film doesn’t linger in despair. Instead, it gently reminds us that restoration starts with acknowledgment, with looking back before we move forward.

What strikes me most is how this work reflects a broader shift in Latinx artistry. Bad Bunny isn’t content to stay in one lane. He’s part of a new generation of multidisciplinary creators who refuse to be boxed in. He’s a reggaetonero, yes, but also a provocateur, an activist, and now, a filmmaker. His expansion upon his music feels seamless because his storytelling has always been cinematic. His songs paint pictures in your mind, and now he’s simply bringing them to life on screen.

This signals something bigger than just Bad Bunny’s own evolution – it’s a call to action for Latinx artists everywhere. We don’t have to stay in our “assigned” lanes. We can mix mediums, experiment, and use every tool at our disposal to tell our stories. In a world that often reduces Latinx creators to stereotypes or singular narratives, Benito is irrefutable proof that we are multifaceted and endlessly innovative.

And yet, DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOTos doesn’t scream for attention. It whispers. It invites you to sit with its quiet moments and consider your own relationship with memory and impermanence. Like his music, it’s both deeply specific to his experience and universal in its themes. You don’t need to be Puerto Rican or Latinx to feel the pang of longing in this piece, but for those of us who are, there’s an added layer of resonance.

There’s a poetic defiance in this, too. In a world that demands immediacy and oversharing, Bad Bunny’s film feels like a reminder to slow down and savor. It’s a reclamation of time and space, an assertion that our stories deserve depth and contemplation.

DtMF isn’t just a short film – it’s a milestone in Bad Bunny’s journey as a storyteller and a reminder of what’s possible for Latinx artists. By embracing his role as a visual poet, he’s carving out space for all of us to dream bigger and create louder. He gives us a reflection of ourselves, of our communities, of the battles we face to preserve what we hold dear. He asks us to consider what we’ve lost, but also what we might still be able to save.

And for that, I’m not just watching – I’m listening, learning, communing, and sitting at the ready to see what he’ll create next. Because if this film is any indication, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio isn’t just making art. He’s making history.