I once joked that if I died before I had the chance to get married, I wanted my funeral to be a wedding. Explaining a joke is poor etiquette, but this one warrants elaboration. I have never felt the urge to have a child or become a parent, but I have always wanted companionship, to be a spouse. Like many others socialized as women, I fantasized about the culmination of that romance: my wedding. Abundant celebrations with the person you love, dazzling proclamations of commitments to each other with everyone you cherish – weddings are nothing short of glorious to me. If I die before I get the chance to know what that’s like, I will be heartbroken. I want a wedding before death.

This is the unfortunate moment in which I admit I mildly identify with the self-obsessed thesis of Jennifer Lopez’s insane film This is Me…Now. Who could guess that this is the movie I mention after talking about my own mortality? In her opening monologue, Lopez says, “Whenever someone asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, my answer was always ‘in love.’” While my romantic impulses never outweighed my work ambitions – I always answered that question with a career – This is Me…Now captures a romantic obsession imposed upon women, especially Latina women. Though I identify as nonbinary, there are moments in which I still struggle with the feminine insecurities and desires intertwined with my culture.

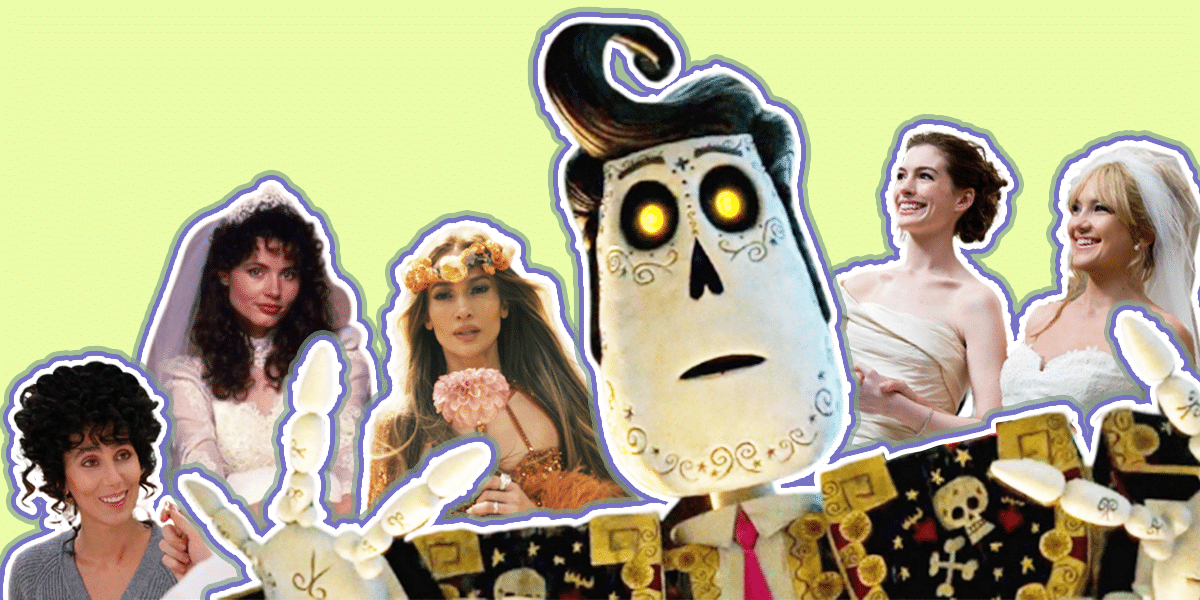

This is Me… Now is just a recent (and rather comical) example of how the wedding films I resonate with reflect common fears about how we choose to love, live, and die. At the very least, JLo’s filmography and autobiography sets up a greater conversation about the Latinx culture of worshiping romance and its shortcomings. Traditional, heterosexual weddings are not a catch-all for happiness or success, regardless of what family may have you believe. They’re also interestingly tied up with death.

Actually, it’s a PG animated film that best captures how weddings, death, and Latinx culture intersect. The Book of Life follows religious figures of the afterlife, La Muerte and Xibalba, betting on the potential romance between childhood friends. Not only is marriage pressured onto lead María supernaturally, but physically, as her father insists she marry Joaquín to ensure their protection. But Manolo and María connect the most. Like the rose and the hummingbird myth referenced in Lopez’s film, there must be dissociation from a living body to win love. Manolo dies thinking he will reunite with a (secretly) comatose María. For our community, a relationship cannot simply be worldly – the burdens of tradition and familial judgment make that unattainable. True romance must be mystical, painful, teetering between the altar and the grave. Perhaps that is why Lopez swings so dramatically on the pendulum between astrology and self-indulgent ego, trying to preserve relationships so sensitive to the forces of time.

The best wedding films subvert expectations, some even existing adjacent to the fateful ceremonies. It’s unbelievable that Bride Wars has a Rotten Tomatoes score 65% lower than This is Me… Now when it’s Anne Hathaway and Kate Hudson being beautiful and unhinged! When brides-to-be Liv and Emma visit their dream wedding planner, Marion St. Claire, she begins with, “A wedding marks the first day of the rest of your life. You have been dead until now.” The women let their ridiculous obsession with these ceremonies trump their friendship, learning that they had more humanity when they were “dead.”

Some films weave weddings and death much more literally. In Beetlejuice, aside from a miniature model of the town, the only personal items that remain of the deceased couple, Adam and Barbara, are their bridal gown and tux. Material placeholders of affection that outlive mere humans. The Deetz family uses these garments to summon Barbara and Adam, allowing for the most bewitchingly tragic shot in the film: the couple trapped in their own romantic imagery, their bodies decaying under a bright green glow. “Til the living tear us apart” is a more fitting vow, and their profound unity is disturbed. That their love is wielded as a weapon against their already premature death is a testament to the natural macabre underlying eternal commitment.

The lead in My Best Friend’s Wedding is not getting married, yet the film is the best visual reproduction of my own dreams for a wedding. At the film’s end, when Jules retreats back to the reception alone, her close friend George surprises her from across the dance floor. “Life goes on. Maybe there won’t be marriage… maybe there won’t be sex… but, by God, there’ll be dancing.” That’s what I look forward to most at my wedding: dancing and seeing others dance. When I die, I want others to remember the musicality of my life and my affection and know it was for them to bask in too. Weddings, like grief, are vulnerable demonstrations of love everlasting.

Naturally, this conversation leads to widows in cinema, as they are at the delicate center of love and death. In Moonstruck, Loretta blames her husband’s passing on their not having a proper ceremony, instead opting for a city hall “I do.” And yet, she happily says yes to Ronny’s unconventional proposal in her kitchen. Death is everywhere in Moonstruck: in Loretta’s father who can’t cope with his aging, in her fiancee Johnny’s dying mother, even in Loretta and Ronny saying they were in a spiritual death before meeting. To be loved is to be reawakened to the parts of yourself you let die out. Though the family is Italian, Moonstruck speaks to the immigrant and future generations’ experience of love in the States, intertwined with the fear of disappointing ancestors who worked hard to form a family tree. It’s about yearning to meet expectations of family longevity and personal legacy through upholding a long-lasting union.

Though weddings are magical in how they infuse life into all that is, has been, and will be, they are still heavy with utilitarian meaning and realism. Aside from the costs and the stress, the most pragmatic impression of the ceremony is that one day, this will all cease to be. You will either break up or die.

“Til death do us part” sets us up to reckon with the oddly phantasmagorical glory of a ceremony of love. Women are taught to spend a lifetime preparing for their weddings, while North American culture fails to prepare them for their own death. Though some Latinx cultures lovingly preserve the liveliness of the dead, my Ecuadorian and Cuban household didn’t. I got more comfort around death in predominantly white cinema than through my Latinx identity. In their own unconventional ways, these films make peace with the discomfort by pairing desire and demise, unveiling that both milestones will one day just be memories etched on your tombstone. As mere mortals, we are here to love before we die, and art that marries that duality of existence is worth honoring.