Argentina had the Spiderwoman and Colombia the revolutionary Latina in Noviembre. Not to be outdone, Mexico’s entry to this year’s Oscars — We Shall Not Be Moved — continues Latin American cinema’s recent exploration of how the region’s violent past affects women’s lives. The film (No Nos Moverán, originally) is the feature-length debut of young Mexican filmmaker Pierre Saint Martin. It premiered at the Guadalajara Film Festival and will play for a week in New York and L.A. at the end of the month as part of its Oscar-qualifying run.

The story focuses on a retired lawyer who is still scarred by the violence Mexico experienced during the “Tlatelolco Massacre” in October of 1968. This was a dark episode in the country’s history where military forces shot upon unarmed student protesters in Tlatelolco Square, some say under pressure from U.S. authorities to quell anti-American unrest in the country ahead of the 1968 Olympics.

With its dark humor and charming central character, We Shall Not Be Moved continues the welcome trend in cinema of reminding audiences that geopolitical flashpoints shape the lives of all peoples, not just the men typically at the center of those stories. The Tlatelolco Massacre has been a mainstay in Mexican cinema since the tragedy itself, with grim features like 1989’s Rojo Amanecer carrying the scars of the past forward into the present. This is the first film on this subject matter with a central female protagonist, however.

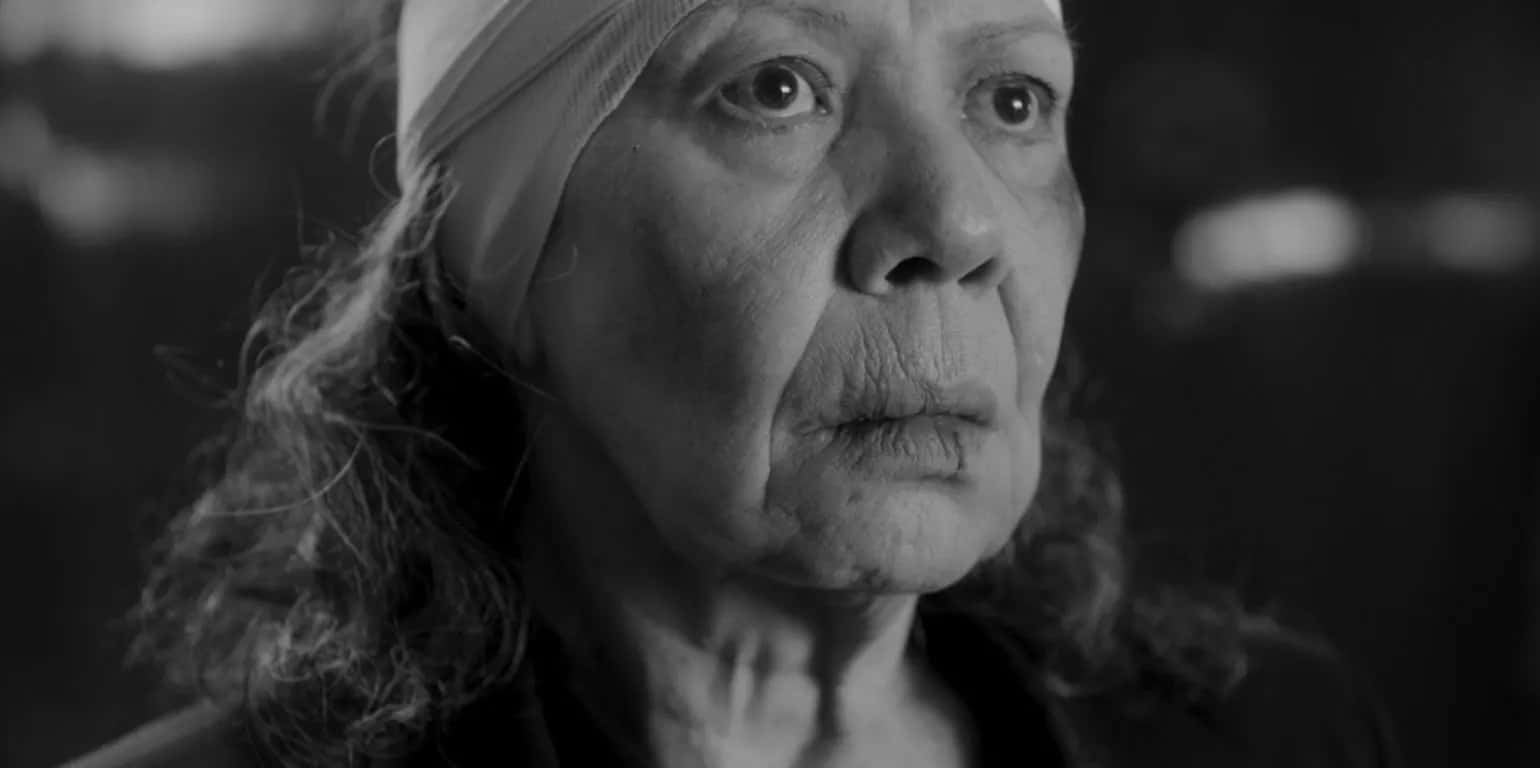

The movie stars Luisa Huertas as Socorro. Huertas delivers a gritty, physical performance that is both deeply moving and profoundly sad. Nearly 60 years ago, her older brother was killed during that night of senseless political violence in Mexico. It was a time when one-party rule and U.S. influence infected the country and the region with bloodshed, to the benefit of unspoken imperialism and the detriment of its people. The past may be distant and the current circumstances changed, but the bitter memories linger all these years later, both for Socorro and for those who inhabit her paranoid world.

For all these years, Socorro has been obsessed with finding her brother’s killer and bringing him to justice. This fixation has strained her relationship with her son and daughter-in-law, and with her very elderly sister, who lives in fear of Socorro. Socorro is a no-nonsense attorney who counsels clients on the legal and practical solutions to their problems. She is a survivor and a fighter. She smokes cigarettes unabashedly in her cluttered office and moves about restlessly and carelessly as she doles out advice, critiques, and tough-love insults. Her straggly salt-and-pepper hair gives her a witch-like aura. She is a little bit off, but also impossible not to fall for her with her charming wit and affection.

But beneath the steely exterior is a woman whose soul has been at least partially eroded, consumed by a lifetime of bitterness and rancor. The film asks: What is the point of such an all-consuming thirst for vengeance? It reminds us of the adage that violence begets violence and urges us to reconsider whether it has to be that way. And when one of her minions finally delivers what could be a case-breaking clue as to the whereabouts of the man she suspects pulled the trigger, Socorro’s purpose in life appears to be coming into a tense, violent focus.

As We Shall Not Be Moved plays out, we discover that it is not just Socorro whose outward appearance may be hiding deeper secrets. The movie itself exhibits Socorro’s two different facades. Socorro’s quest may be oppressing her, but it has also given her something to live for all these years. True to the Latin American experience, Saint Martin sees the value of nostalgia, no matter how melancholic it may be.

This is the appeal of this film and many others like it that have recently come out of the region. Their portrayals of the past through female characters urge us to rethink our relationships to some of the harder chapters in Latin American history. The title of the film, “We Shall Not Be Moved,” refers nominally to a slogan that the Tlatelolco protesters chanted to resist the government. But it also refers to the reality that the country will not — or perhaps should not — be moved away from its past. Our history, however complex, is what makes us rich. The film is shot in a stunning black and white, not only because Socorro is living in the past, but because the past haunts and molds the present.

In the end, We Shall Not Be Moved effectively confronts the perpetual trauma of historical violence by highlighting the complexity of women navigating its aftermath. It reminds us that healing and understanding are perpetual processes. And by doing all of this through a female protagonist, it challenges traditional portrayals of historical events. It reminds us of the power in changing whose stories are told and remembered. We Shall Not Be Moved does not need an Oscar nomination to be the great film that it is. The question nevertheless remains—will the Academy continue to shy away from stories that are not familiar to its core constituency and favor European ones? Will it do so when Latin America has offered up, yet again, such a complex, beautiful tapestry of choices? We shall soon find out—but we shall not be moved from our quest to bring awareness to this issue.