Engel asks what lies we’ve been told about immigration and why

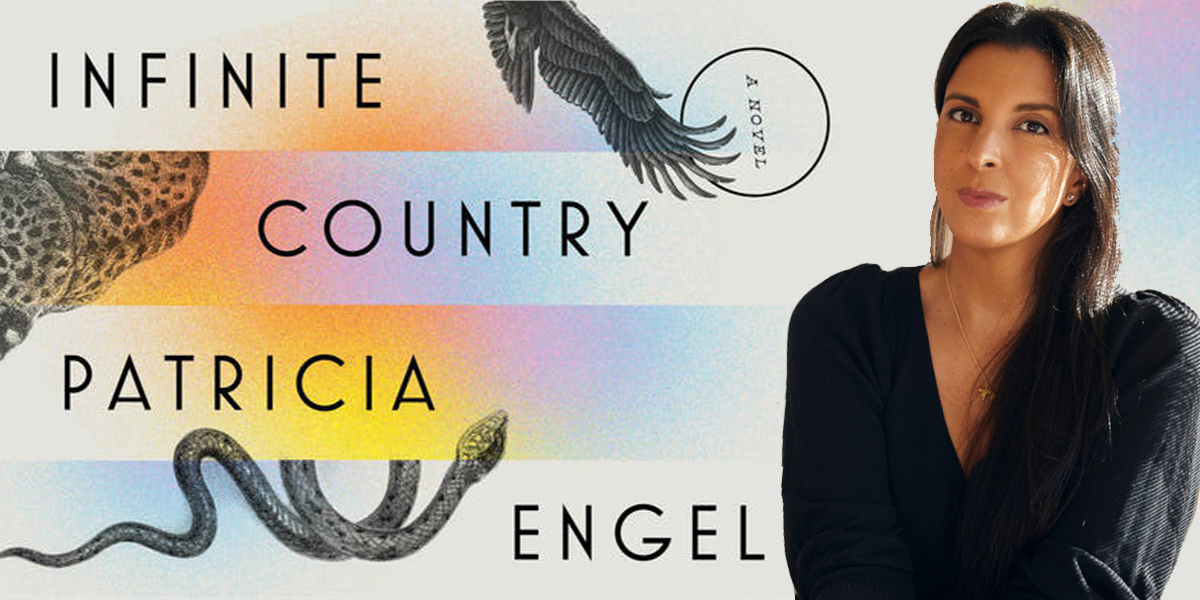

PEN/Hemingway Finalist Patricia Engel is out with her fourth book this month, Infinite Country. It chronicles a family’s immigration to the United States from Colombia over the generations.

The novel starts with Talia’s escape from a correctional facility miles away from Bogota, her ticket to the United States waiting for her. Originally born in the States, Talia would grow up in Colombia with her father, Mauro, and her grandmother, Perla. After years of separation from her mother, Elena, and her two siblings, this could be her last chance to reunite with her family. The novel takes us beyond and before Talia’s flight, tracing her parents’ immigration journey over the span of twenty years.

A first-generation American herself, Engel writes from a well of intimacy that animates the story of this bi-national family. In this short but epic book, the author tests her skills, writing across time, language, culture, and myth. Shanti Escalante-De Mattei and Patricia Engel got on the phone to discuss Engel’s journey to become a writer, the barriers she faced, and how Infinite Country responds to the lies we’ve been told about immigration. Check out our conversation below edited for clarity.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: Were you inspired by your own family’s history, navigating immigration?

PATRICIA ENGEL: Yeah. All my books explore immigration and diaspora in different ways, be it by first- or second-generation immigrants. I’m the daughter of Colombian immigrants. It’s the way that I occupy my body, the way that I see the world, the way that I’m seen. So I’ve always been drawn to that space, because that’s my community. That’s my world.

I’m the daughter of Colombian immigrants. It’s the way that I occupy my body, the way that I see the world, the way that I’m seen.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: When you were younger, were you exposed to literature from the diaspora and Latin America?

PATRICIA ENGEL: Yes, I was exposed to it because my mother was a big reader, so I was always reading as much as I was available to me in Spanish, not American literature. I’m old enough that I come from a time when I was not given a single book by a single diasporic Latin American writer to read for the entirety of my education.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: Including your MFA?

PATRICIA ENGEL: No, I took a literature class, a Caribbean literature class in my MFA, in which the professor assigned, Let It Rain Coffee by Angie Cruz. That was the one. I’ve always told my students, “Do not depend on your education to be your education. You have to be responsible for educating yourself further. You have to read the things nobody is telling you to read. You have to take it into your own hands and push it.” Because then what happens? You only read what someone is telling you to read.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: Speaking of your education, how did you start off writing?

PATRICIA ENGEL: I was writing since I learned how to write letters and put them together. I come from a really creative family of artists and musicians. My grandmother is a writer, but she never published anything so I didn’t know any professional writers. I didn’t really know how one went about making a life as a writer. The example that I have was my grandmother who had nine children and a whole bunch of grandchildren and yet, she still prioritized her private writing time. So that’s really how I started, I would just write for myself to entertain myself and keep myself company because I was lonely. I never showed my work to anyone, not even my own parents. And when I went to college, as most first generation college kids, I had to figure it out largely on my own. I didn’t even know you could major in creative writing, nobody told me. I was not the kind of student that drew the attention of teachers or professors.

After I finished college, I worked for a number of years in New York and I would take continuing education classes, writing workshops at night, things like that, just so I could be writing. I used to go to the Barnes and Noble on Union Square where they have this magazine section on the second floor. That’s where I discovered poets and writers’ magazines, which is where I learned about MFA programs. I decided to apply and I got into one. And I thought, “Well, this is cool. I can quit my job and write for a couple years. Then when I finish, I’ll just go back to work.” It was a three year program, [and] I just wrote like crazy. I started writing stories and very slowly, I started publishing them here and there. I won a couple of contests. Then a year after I finished my MFA, I got my first book deal, which was for two books.

I just knew that I wanted to write about a family and how a family remains a family across time and across borders, even when they are being constantly challenged.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: Infinite Country is now your fourth book. Was there any particular events that inspired it?

PATRICIA ENGEL: Infinite Country is the result of a lifetime of knowing and caring about so many people who have been in situations very similar to the ones that the family in Infinite Country is experiencing. It’s a story that has grown with me over my entire lifetime.

But in terms of the actual construction of the novel, which I only sat down to write about three years ago or so, I just knew that I wanted to write about a family and how a family remains a family across time and across borders, even when they are being constantly challenged by the uncertainty of ever-changing immigration law.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: As a first-gen American myself, it’s been this long term process, realizing how much my parents went through. What was it like reaching so deeply into that experience through Mauro and Elena–the parent’s perspective?

PATRICIA ENGEL: I think that many immigrant families keep their story alive in a very vivid way, because you’re constantly living the story of how we got here, the homeland that we left, and this new place that we’re in now and the life we’re trying to make here. You’re constantly aware of that as a first-generation kid, so a lot of my work was concerned with that story.

I really dove deep into the experience of the parents; I went back into their childhoods. That was new for me and maybe that’s something that I wouldn’t have been able to write earlier in my life. I think I had to maybe get to a certain age or mental space to really be able to consider the journey of these teenagers who fell in love and became parents and made a family together and what that whole experience of taking their family to a whole new world, what that must have been.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: There’s this passage where Elena is thinking about her daughter, it goes, “Elena imagined it was Talia, the daughter she did not raise yet who had grown up in the same home as her mother, who knew her best.” As part of the diaspora was there a sense of removal between what you could and couldn’t understand about your parents? Was that particularly animating for Infinite Country?

PATRICIA ENGEL: You can’t deny the facts. The fact that you have had an entirely different upbringing in an entirely different country and culture from what your parents had. There is sometimes a cultural gap that exists within families as a result of migration. I was writing into that [gap] but also the gaps that exist even when you do grow up the same way. There is always an unknowable space that exists between parents and their children. Everybody has a secret self, and everybody has an interior life. Infinite Country gets at that private experience of immigration in the five different family members. There is what’s “obvious” to everybody about what one’s life consists of as a result of immigrating. But there’s also what they carry inside and what they don’t say even to each other.

There is always an unknowable space that exists between parents and their children. Everybody has a secret self, and everybody has an interior life.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: Much of Infinite Country was written in a kind of summary style, what went into that decision?

PATRICIA ENGEL: In some ways, it’s a story about storytelling, right? Because what are we besides the sum of the stories that we’ve heard, that have been told to us, and the stories we tell ourselves about who we are, and the space that we occupy on this planet?

You find out that the novel is being narrated by one of the children, who is sort of the family witness. You realize that you’re reading a family chronicle and that every family has their own story of how they came to be, how they got to the United States, because most families came from elsewhere–even those who seem to have forgotten that.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: Could you tell me a little bit about the research that you did for Infinite Country?

PATRICIA ENGEL: I do tons of research, no matter what I’m writing. Infinite Country is largely set in Bogota, my mother’s hometown where I still have a lot of family and a place that I go back to as frequently as possible. So a lot of what goes into Infinite Country is built upon the roots of my life, but then also additional research. An obvious example of that is the Andean folklore, ancestral knowledge that figures in the story, and also the nuances of the migratory process, the legal issues, all those little intricacies.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: And immigration laws change all the time, as we know. Why did you write Infinite Country in that particular span of time?

PATRICIA ENGEL: Infinite Country begins in the late 1990s and it follows the family over twenty or so years, ending around 2018. This was a really pivotal time in the way that foreigners are viewed and described in the eyes of the United States, media and the public, following the turn of the millennium, 9/11, and the [subsequent] creation of the Department of Homeland Security, which gave way to ICE.

I hope that what people see in the novel is how the perception of foreigners–as a menace, as a drain on society–was very quickly manipulated for special interests and political purposes. I’m old enough to remember a time when it was not like that. When amnesties were given a lot more freely, when the laws seemed to be more in favor of helping people. There was quite a rapid shift and I hope that that’s evident in the novel.

I wanted to [address] the popular stereotype of the immigrant who just comes banging on the doors of the United States and once they’re here, they never look back. In my experience, with all the people I know who’ve gone through that process, there is so much regret and doubt and longing and profound homesickness, wondering if you made the right choice.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: In Infinite Country, you showed what an agonizing choice it is to leave, to stay, that those choices are being made every day. Was that at all in response to those who ask, “Why don’t you go back to where you came from?”

PATRICIA ENGEL: I would never address something as silly as that sort of pointless question. And the person asking that question should ask–why don’t they go back? The fact is everybody in this country, aside from Indigenous peoples, has an ancestor who either by choice or by force, was that disrupter in the family line, the one who left the original homeland and came to this one.

Mauro and Elena don’t leave with the intention of immigrating permanently. They come on tourist visas to the United States, and they overstay, which is a very common circumstance. A lot of people become immigrants accidentally or just circumstantially. It just kind of happens as a result of the accumulation of days that become months and then years. Next thing you know you have a whole other life in a new country.

I wanted to [address] the popular stereotype of the immigrant who just comes banging on the doors of the United States and once they’re here, they never look back. In my experience, with all the people I know who’ve gone through that process, there is so much regret and doubt and longing and profound homesickness, wondering if you made the right choice. Thinking about that life that you’ve left, because the life that you love goes on without you. A lot of people never get over that. It’s a great burden to bear, to be the one that leaves your homeland and makes [life] different for your generation and the generations that follow. You become the one that changes the family history.

The human species is a migratory species, it’s a completely natural condition. We’ve just been socially conditioned to look down on it – that’s one of the great lies of society. We need to look deeply into that and wonder – who is it serving?