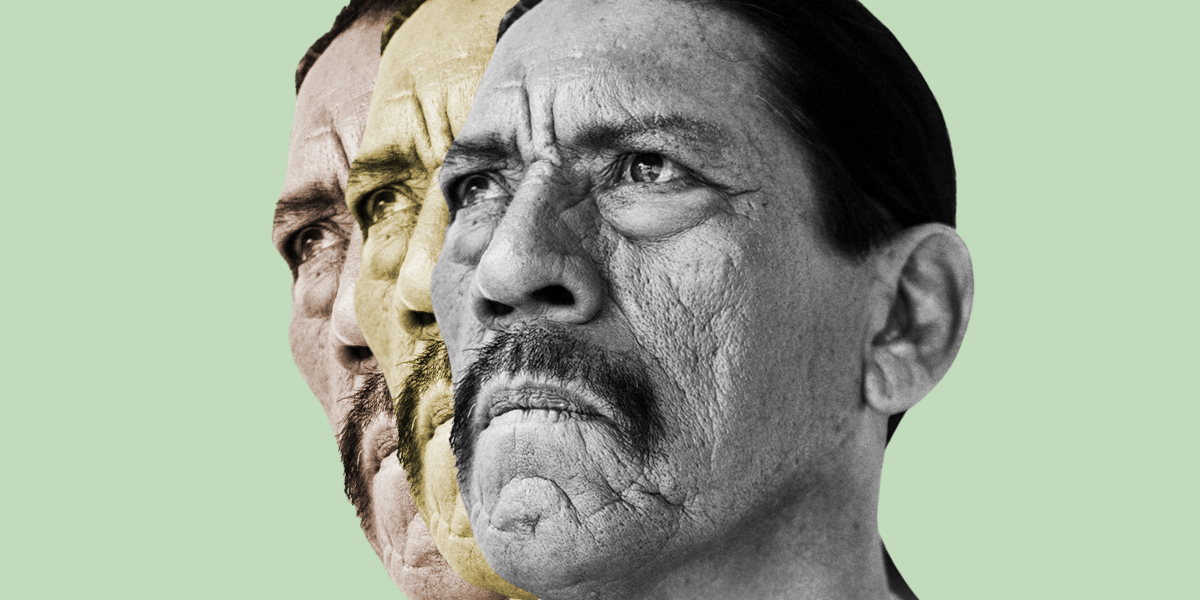

The first time Danny Trejo heard the phrase “toxic masculinity” he was 74 years old, and as you can imagine, his first response was, “What the hell is toxic masculinity?” This is Machete after all. The man whose gruff voice and menacing looks have become the prototype for the quintessential, Chicano tough guy. But after talking it through, he suddenly had a better understanding of himself and the ways growing up in an environment of machismo impacted him. In his New York Times best-selling book, Trejo: My Life of Crime, Redemption, and Hollywood, Danny Trejo explores how he became trapped by toxic masculinity and how he finally broke free.

Our first impressions of gender norms and roles start at home, and for Trejo, growing up in a Latino household in the 1950’s, meant no “sissy” behavior. “[I] had to be masculine in every way at every moment. One day at lunch at Elysian Heights Elementary the teachers brought the kids together to do a mass Hokey Pokey. I had already been so indoctrinated in the macho Chicanismo of my father and his brothers, I wouldn’t do it…” he recalls. Participating in something as innocent and trivial as dancing with his classmates meant being hit or humiliated if his father ever found out. Being around other family members who shared the same temperament and beliefs about manhood was no easier. By the time Trejo was 12, he began using heroin as a means of escaping the turmoil he experienced at home where the only acceptable emotion was rage.

In the many years that followed, Trejo struggled. Unable to cope with his feelings and under the influence of drugs, he channeled his emotions into solely aggression. In time, fights, drug-dealing, and robbery landed him in prison where he served time off and on from 1956-1968.

While he was eventually freed from prison and able to overcome addiction (he devoted his time to helping others recover, both through volunteer efforts and full-time work with rehab clinics), the relationships in his life remained a challenge. Growing up around men who lived the phrase una en la casa y una en la calle influenced Trejo more than he was aware of. He married and divorced multiple times, mostly due to infidelity, “I didn’t look at marriage as a lifelong commitment or a sacrament. I saw it as an opportunity for a good party… something to do until I didn’t feel like doing it anymore.” He also added, “If you were going to be my old lady, the other women were just something you had to get used to, and your feelings about them didn’t rate. I was the only one allowed to have feelings in my house, just like my dad.”

Although he was like his father in some ways, Trejo broke the cycle of abuse and was a loving and devoted father to his children. It was through his relationship with them (along with sobriety and faith) that he began to change and realize certain beliefs of his were outdated and hurtful. About conversations he had with his daughter, he stated, “I realized that when I said things like that about women, I was saying them about her… she helped me see all the women in my life in a different light. I was beginning, in a way, to endow women with the humanity that they always deserved” – something Trejo previously believed only to be given to men.

It takes a lot for anyone, especially a Mexican-American man of Trejo’s generation, to develop the self-awareness that it takes to better understand where his behavior was coming from and change it for the betterment of himself and those around him. Trejo was deeply hurt because of the machismo he grew up in, but realized it doesn’t have to be that way. I hope Danny Trejo’s first-hand account helps other Chicanos look within our culture and consider redefining masculinity. It’s time.