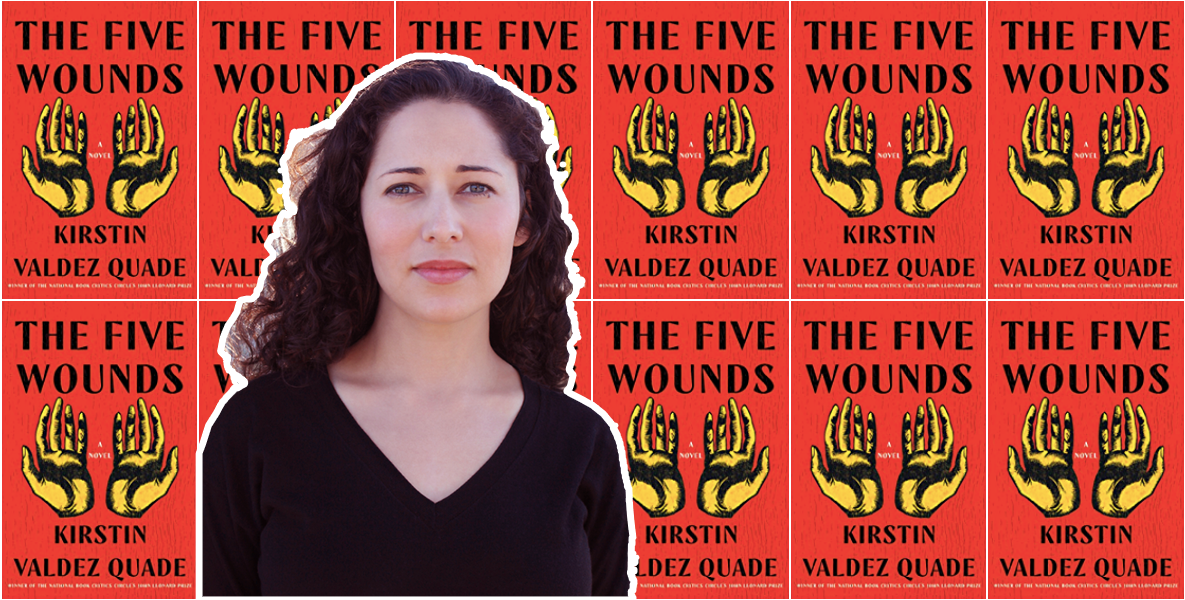

Kirstin Valdez Quade’s debut novel The Five Wounds is just out. Originally a short story by the same name, Valdez Quade’s new novel is about a family grappling with addiction, unemployment, teen pregnancy, and illness in a small New Mexican town.

Angel is 15 and pregnant but trying her hardest to give herself and her son what they need for a good life. Amadeo, her father, is an unemployed alcoholic who is hoping that religious penitence will change him. Yolanda, his mother and Angel’s grandmother, has kept the family together through years of hardship but she knows her time to help her family is rapidly running out. In the hands of another author, this story could have easily devolved into a pitying portrait of poverty and struggle, but Valdez Quade manages to weave together an incredibly touching story of redemption.

Shanti Escalante-De Mattei and Kirstin Valdez Quade got on the phone to discuss the religious fraternity of penitentes in New Mexico, the inspiration behind the story, and the colonial violence that shapes our communities today.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: When did you know you wanted to be a writer?

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE: I announced fairly early on that I want to be a writer [laughs]. That didn’t necessarily mean that I was writing or that I knew what that meant, but I was always a big reader. Reading was such an important solace and escape for me. When I was a kid, we moved a lot and so we were often on the road. My dad is a geologist and we spent a lot of time in deserts. There was a lot of waiting around for him as he did his research, and I read through all of that in the back of our Volkswagen van. When we would move to a new town or when we would pass through towns, I was constantly watching and wondering what people’s lives were like. So that was probably the beginning of my life as a fiction writer – just imagining stories and imagining other lives. It wasn’t until college when I started taking writing workshops and began to actually meet real writers, to see real writers who are living and working, that I began to imagine what a writing life could be like.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: The Five Wounds was originally a short story that appeared in The New Yorker. What was the initial inspiration for that short story?

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE: Inspiration always seems to come from several different directions. At the time, I was working as a grant writer for a consortium of nonprofits in Tucson, Arizona, that were working to improve accessibility for quality daycare for families. I went on a site visit to a teen parent program and I was so struck by these young women, these girls, who were in the program. They were at once incredibly young, you know, kids, but also really mature and poised and earnest about the important work of making a good life for their children. I was just so moved by that and also delighted by their energy.

I was also reading about the history of penitentes in northern New Mexico. In one of the books I was reading about the penitentes in the 19th century, there was a line about how there were rumors of a penitente that was actually being crucified. That’s not a part of the tradition as it is today or even the tradition as it was then but there were some undocumented rumors that this had happened. And I was just really interested in what would be the need and the sort of depth of feeling and belief that would lead a person to do that. That was the beginning of Amadeo.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: When did you know that you wanted to expand your short story to make this novel?

I always found physical penance to be really moving. It always seemed like a deep and empathetic way of trying to engage with the story of Christ’s crucifixion. I always thought it was really beautiful.

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE: I was asked about [making it into a novel] after the story came out and I completely dismissed it. It wasn’t until two years after [later] that I was looking at some other stories that I was writing and I realized they weren’t really going anywhere. I suddenly realized that they were all dealing with the same basic family dynamic, the same basic cast of characters. I mean they all had different names, but it was essentially the same family and I thought, “these characters are still with me and I’m still interested in them.”

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: Could you tell me a little bit about your initial interest in the penitentes?

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE: It’s a tradition that anyone from New Mexico grows up hearing about and knowing about. I sort of peripherally knew of practicing penitentes: my mother’s English teacher and my grandmother’s friend’s boyfriend. So it was something I was always aware of and very interested in as somebody interested in the tension in enacting faith through pageantry and the tension between faith and doubt. I always found physical penance to be really moving. It always seemed like a deep and empathetic way of trying to engage with the story of Christ’s crucifixion. I always thought it was really beautiful.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: I had no idea that tradition was still alive in New Mexico.

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE: The numbers are much smaller now. Now in the 19th century, the membership rolls were in the hundreds and they really fulfilled central social purposes. These villages would often share a priest among many so these lay communities sort of grew to fill those needs. There are pockets all over the world where these sort of older practices are still alive, like in the Philippines and other parts of Latin America.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: I wanted to get into your conception of yourself as a Latina because it’s already a very murky and wide designation. Being Latina and being Hispanic in the US is so often defined in relation to immigration and the border. But for many people in Texas, New Mexico, and other states, the people didn’t move, the border did. Was that the case for your family?

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE: Yes, absolutely. It’s a very specific community and identity in northern New Mexico, at least. Families have been there for so long.

When we started moving when I was a kid, I definitely felt some confusion about what I was because different aspects of your identity become more salient in different contexts. When I was 12 we moved to Tucson – a largely Mexican American community. I think my sister and I had some confusion about who we were, what we were. We weren’t quite Mexican American but we weren’t not.

It’s funny, I did notice that in some reviews of my first book, some people wrote that I wrote about the immigrant experience. That really surprised me because that’s not an experience I’ve had, (certainly friends have).

We weren’t quite Mexican American but we weren’t not. It’s funny, I did notice that in some reviews of my first book, some people wrote that I wrote about the immigrant experience. That really surprised me because that’s not an experience I’ve had.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: That does sound really confusing! And frustrating too. Were you given tools to understand this aspect of your history and heritage?

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE: The identity question became more confused, actually, when I went to high school. I went to a boarding school in New Hampshire and I remember I took a colonial American history class and it was focused on the English colonies. I thought maybe in the second half of the class, we would talk about Spanish colonization in other parts of the United States. But that never came! I remember asking the teacher if we would learn about that and he said, “No, that’s not colonial American history,” which was very confusing to me because it is. I think that history is not well understood, the long-term effects and pain of Spanish presence are not terribly well examined.

SHANTI ESCALANTE-DE MATTEI: You can see the nuances of that history in The Five Wounds. There’s a passage where Yolanda is talking about the beginning of violence in the community and in the family and she just tracks it all the way to that first conquistador who made an unwilling wife out of an Indigenous woman. We conceive of that type of narrative as something that was happening in Latin America but this is also an American story.

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE: The effects of that violence are palpable today. We see it today. You know in 2020 with the tearing down of the Juan de Oñate statue in Albuquerque and the right-wing militia that showed up to defend that brutal, brutal man. I mean he was so brutal that the Spanish crown reprimanded him and the Spanish crown was okay with the Inquisition! We need to contend with all of the origin myths in this country. We need to contend with that one.